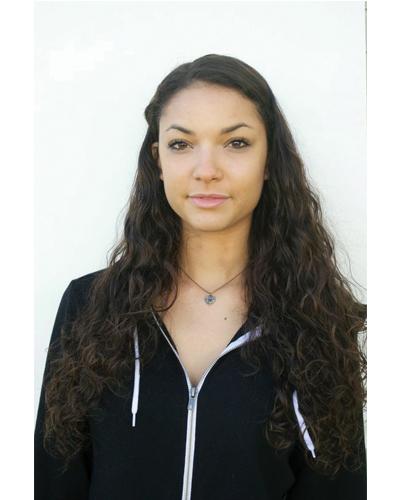

Eden Schwartz is alone, wandering the Grant neighborhood with a sense of aimlessness about her. It’s 2004. Schwartz, a Grant High School freshman at the time, has virtually dropped out.

She should be in class. Instead, she spends her days tripping on almost every curb and crack in the pavement as she stumbles through streets that have become all too familiar.

Today, about 10 years later, Schwartz is across the country attending graduate school at New York University. It hasn’t been an easy feat for the young woman who graduated from Grant in 2007.

After a childhood filled with excellence, the last decade has been filled with extreme struggle following a traumatic car accident. It was an incident that left Schwartz in a physically and mentally damaged state that she only recently put behind her.

Her childhood was unorthodox. As a child, Schwartz was a highly motivated, intense and sensitive girl. “I wanted to be a doctor and run an orphanage at the same time,” she remembers.

Schwartz was unusually interested in intellectually mature subjects. Her mother, Tracey Durbin, recalls times when Schwartz would recite Shakespeare from memory. By the age of 4, she would sing instead of speak. She wrote songs at 9 and played the piano at a level far beyond her age.

Schwartz’s father, who split from the family when she was just a year old, lived in Los Angeles, while her mother lived in Portland. She fondly remembers going in between the two cities frequently.

She attended Sunnyside Environmental School in Portland. During recess, Schwartz could often times be found in the classroom, playing a game of chess with her teachers. Social interaction was not typical. “I was a big nerd,” says Schwartz, now 24. “I wasn’t really focused on having friends.”

She used her smarts to her advantage and skipped seventh grade. Despite her lack of social skills, Schwartz focused on academics and worked her way to the top of her class. When she started high school at Grant, she continued to have a small social presence. But it was a never a principle concern. Instead, music and theatre began to dominate her life. Her grades remained strong, as Schwartz continued her straight-A reputation.

In November of her freshman year, Schwartz and Durbin were in Arizona visiting Schwartz’s grandmother. Near the end of their trip, they got in a taxi headed toward the Tucson airport to catch their flight home.

Minutes later, the taxi ran a red light and was t-boned by another car. They spun around three times and slammed into a lamppost on the side of the road. Her mother, a dancer, was injured so badly all throughout her back and hips that she had to stay in an Arizona hospital, unable to return home.

Schwartz, on the other hand, left the scene with a slightly swollen neck. She met her dad at the airport in Portland that day. He had flown from Los Angeles to Portland to take care of Schwartz and her brother while their mom was in the hospital.

With her mother seriously injured, the focus was drawn away from Schwartz. She returned to school. “I came back and I was functioning, just with headaches,” she recalls. But within a few weeks, her personality began to change dramatically.

Schwartz became an insomniac and struggled with depression. She now describes her condition as similar to Tourette’s syndrome, where the malady makes you randomly say things without meaning to say them. “You can’t see a head injury,” says Durbin. “To everyone else, she looked fine. People thought she was just being a teenager.”

At the time, her family didn’t yet understand the extent of her injuries. It wasn’t until her counselor, Diallo Lewis, sat down with her. “He called me in the hospital in Arizona and explained that he had met her before the accident, and this was not Eden,” recalls Durbin. “He alerted me and another friend told me to get her a doctor.”

“It was really impacting her performance at school,” remembers Lewis. “Both Eden and her mom – they were a great family to work with.”

“I don’t know if I can’t remember freshman year or if I blocked it out,” says Schwartz.

A month after the accident, she stopped coming to school.

“It was like she would get up in the morning and just be unable to get herself to classes,” her mother remembers.

Because she was acting so drastically different, Schwartz was placed in special education classes. But so much was happening that she barely seemed to notice. “I was just so out of it,” she recalls.

She also became extremely hard on herself. She had been a straight-A student, but could now barely see the desk in front of her. Her mom had put her on several medications at different times, but none of them seemed to work.

Things started looking up when Schwartz took her first trip to a neuro-ophthalmologist. “I walked in, and he looked at me and told me he was going to get me feeling better,” she remembers.

Upon asking him how he knew something was wrong, he explained that her posture was crooked – a common way people try to reduce visual noise.

He gave her special glasses to reduce the amount of light that reached her eyes. “As soon as I got my glasses, I could see,” she says. “Up until then, I was seeing double and triple, and I had horrible depth perception. I even stopped reading.”

Sophomore year marked another upward trend. Schwartz received an offer to play piano for Grant’s performance of “Juliet and Romeo,” a version of the Shakespeare play. “I had been writing since the accident,” she recalls. “It wasn’t my most comprehensive work, but it was music.”

Trisha Todd, the director and drama teacher at the time, went to Schwartz’s teachers and completely changed her schedule so she could dedicate most of her time at school toward the play.

Todd remembers the day she met Schwartz vividly. “Sometimes people come into your life and you just know that person is going to be in your life for a while,” she recalls. “I kind of had that feeling with Eden.”

Todd also remembers the first time she heard Eden perform. “I was surprised seeing someone so shy be not shy to perform,” she says. “She didn’t have any qualms about playing her music.”

Throughout the production, Schwartz mostly stayed separate from the cast. “She wouldn’t participate in the warm ups,” says Todd. “I didn’t really push her. I let her come to me and come to the process.”

“With Juliet and Romeo, I finally felt like I had a base,” recalls Schwartz. “It brought me back into the fold.”

By putting her in special education classes, Grant enabled her to graduate with her class, which was her main goal. “They knew she was a serious girl,” said Durbin. “They were so compassionate throughout the whole thing. They went way beyond.”

“They say brain swelling takes two years to go down, but that’s not true,” Schwartz says. “You have to deal with the repercussions, like the depression, the shame and the embarrassment afterwards.”

Eden couldn’t even focus on having friends until junior year. “It’s a lot to ask of someone to be there during the ups and downs,” she says. “It’s been recent that I haven’t felt hindered by my ability to even process things.”

Todd remembers the time with pride. “Her graduating from high school was a feat in and of itself,” recalls Todd.

Schwartz was still dealing with the residual effects of the medications she took and didn’t want to leave home. However, she was accepted into Cornish University in Seattle, and attended all four years there. Schwartz recalls that her situation didn’t fully settle down until junior year of college.

Schwartz now describes the brain damage as a “separation from reality,” and compares the feeling to drug use. “Alcohol and drugs certainly do not interest me now that I’ve gone through this experience,” she says, as the mixture of her brain damage and medications kept her in a haze for most of her high school years. “I would never electively put myself into that mindset again.”

Throughout the ups and the downs, Schwartz used music to anchor herself. “I didn’t have much of a personality at that point,” she says. “I was all injury. So music was my next step, and after that I became a person. It was the only thing I could do. It kept my voice alive. I’m not sure what I would have done otherwise.”

Now, Schwartz puts most of her energy into music. “Regardless of whether or not I’m performing, I’m writing,” she says. “It’s my favorite thing to do in the world.”

Writing and performing are second nature to her, but she struggles with everything in between. “I’m not very social. I’m not a drinker and I’m not really interested in social media,” she states. “To be a musician these days, you have to be an entrepreneur, promoting yourself constantly. I just don’t have that type of personality.”

Schwartz copes with her lack of ability to self-promote by using her talents to help others. She has recorded and performed music with a diverse crowd, ranging from Seattle’s blind community, children in extreme poverty and high school-aged students who are refugees.

The accident has an impact on every aspect of Schwartz’s daily life. Primarily, it has made her a more empathetic person. It’s also widened her perspective on life and made her appreciate things for what they are. “In time, I also found an increasing amount of compassion and patience emerging for the process of learning and creating,” she says.

It’s also made Schwartz and her mom more mindful. Durbin struggles with post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “I’m definitely hyper-vigilant about things. Any type of sound that seems like it might be scary… It makes you go into a more aware mode,” says Durbin.

While Schwartz has barely any memory of the crash, her mother remembers it vividly. Durbin hasn’t been on a single freeway since then.

This year, Schwartz began her first year of graduate school at NYU and is studying educational theater with an emphasis in arts outreach and working with marginalized and underserved youth populations.

She has come a long way since the crash and graduate school is another step in the right direction.

“I didn’t have much of a personality at that point,” she says. “I was all injury. So music was my next step, and after that I became a person.”