Since 1924, Grant High School has been home to more than 26,000 varsity-level athletes. But only the best of the best are welcomed into the school’s athletic Hall of Fame.

On Oct. 20, 16 former athletes from Grant’s past will be inducted into the star-studded hall at the sixth-annual ceremony.

“It’s the biggest honor Grant can lay on its athletes,” says Gerry Spencer, the chairman of the Hall of Fame committee.

Founded in 2009 by John Keller, a 1951 Grant graduate, the Hall of Fame is designed to honor athletes who excelled in their sports. Each year, 10 board members sit down and sift through a pile of nominations.

“We want people who have conducted their lives in a way that they should conduct them,” Spencer says.

After the induction ceremony, new names and images are put on plaques and displayed at the school. Here are three inductees’ stories:

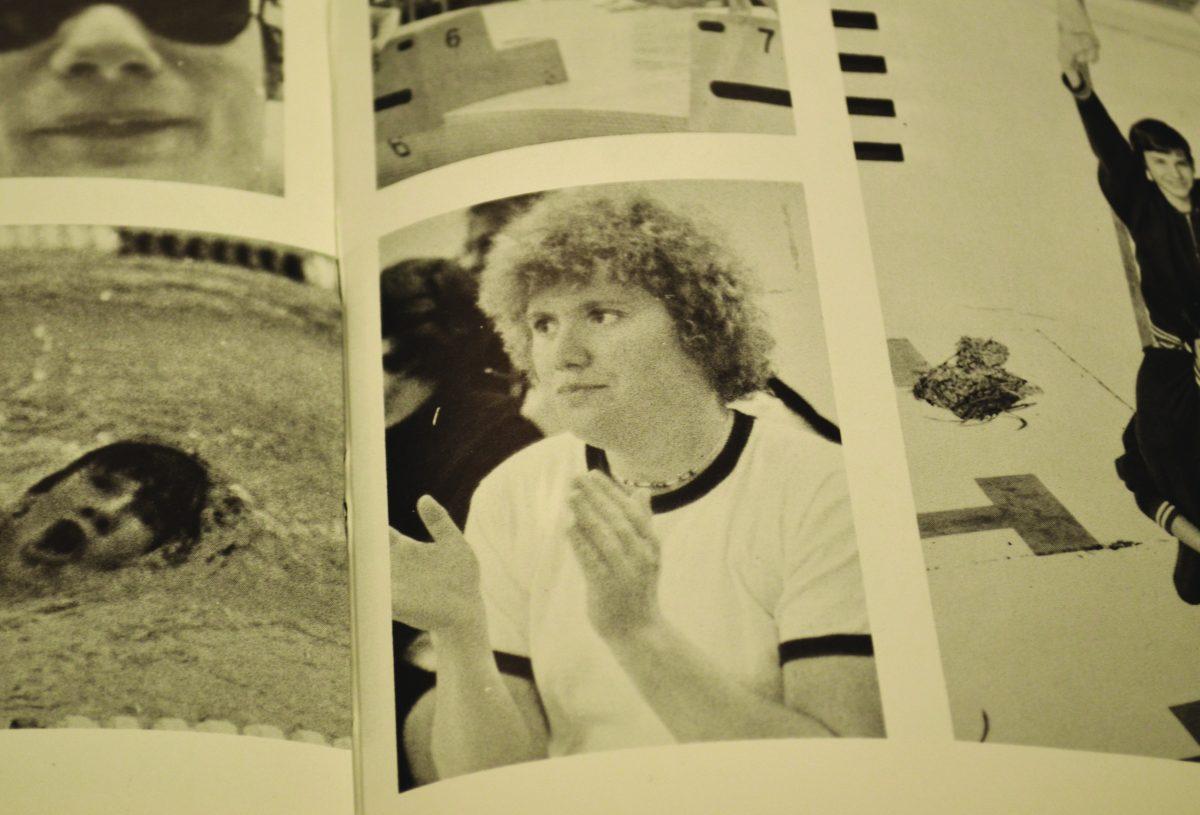

JANICE SHAFFER WALL

Janice Shaffer Wall walks into her living room, proudly wielding a bright yellow and green framed “O.” She had to wait more than 30 years to get her varsity letter from the University of Oregon. Back then, only the male athletes got to take home letters.

“If the house burned down, I would grab my husband and two sons if they were here, and this,” says Wall, clutching her letter.

A former coach and teacher at Grant High School, Wall has been driven by her love for sports. She was a pioneer, an athletic trailblazer. She did it all.

Born and raised in Springfield, she attended Thurston High School. She took first place in discus, third place in shot put and third place in javelin in the first women’s state championship track meet. “We had to wear skirts. It was awful,” she laughs.

After graduating from Thurston in 1966, Wall enrolled at Oregon. While at U of O, she participated in swimming, field hockey, track, basketball and softball. For her talents in the pool, the University of Oregon awarded her an athletic scholarship, informing her that she would be the first woman to receive one.

In 1969, she participated in the first women’s swimming national championship. And thanks to the efforts of Wall and a handful of her peers, a number of women received varsity letters they had earned some 30 years earlier in a 2011 decision by the university.

“It was a hard time for women back then,” Wall says. “We had to battle a lot of things.”

Title IX, a federal law passed in 1972 requiring gender equality in college sports, was not yet in effect. While the male athletes got to travel by plane, her team once had to drive all the way to Louisiana.

“They wouldn’t admit that women could be athletes,” Wall says.

After graduating, she became a health teacher at Grant. “It was an amazing opportunity. I was young and just really lucky,” says Wall, who believes she got the job because of her ability to coach gymnastics.

She taught at Grant from 1970 to 1995 and didn’t miss a single season of coaching. Her sports were swimming, gymnastics, track and field, basketball, volleyball and soccer.

In 1995, Wall left Grant for Illinois after her husband landed a job there. “When I had to leave Grant, it was probably the saddest day of my life,” she recalls.

Wall, now 66, has two sons, both athletic – of course. Both work in Oregon, one as a special agent for the FBI and the other as a teacher.

Wall met most of her closest friends through her years spent at Grant. She often meets them for holidays and vacations. “Grantonians stay together as a family,” Wall says.

ROBERT BATES

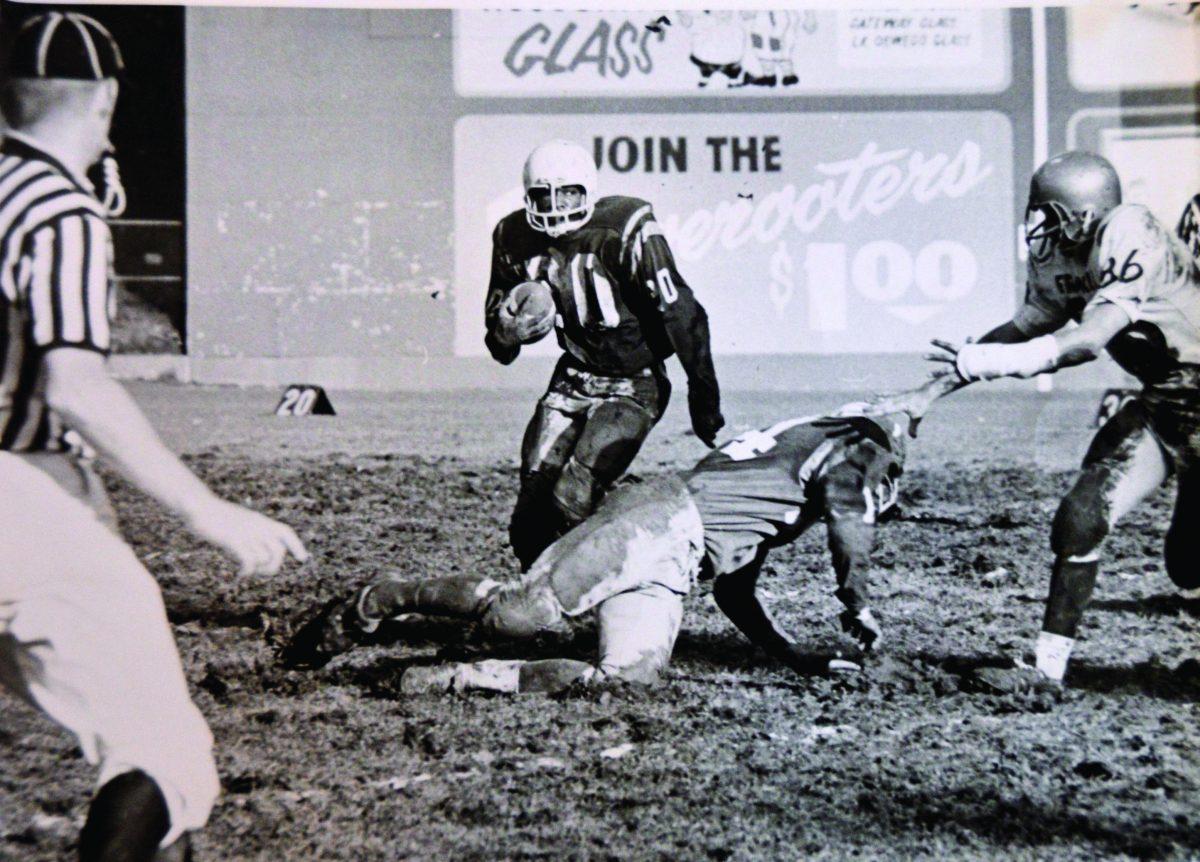

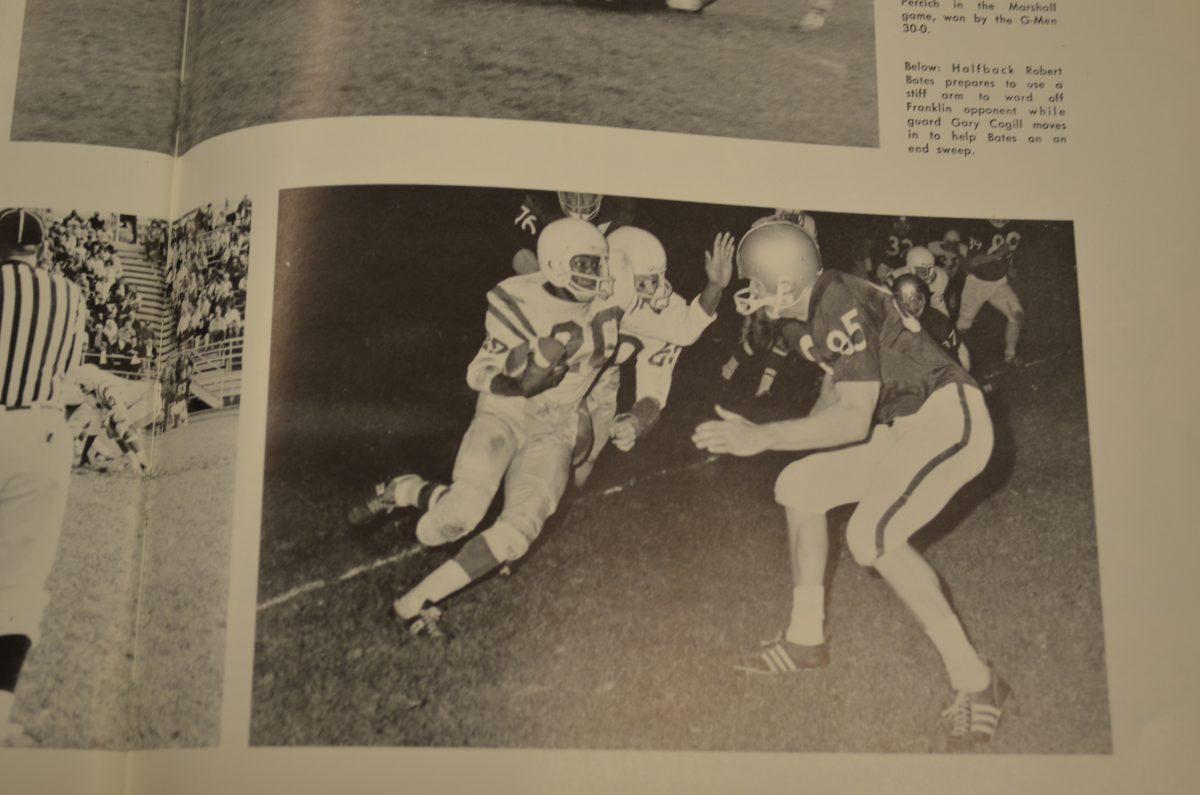

By the time the defense approached for the tackle, it was all over. They didn’t have a chance. Robert Bates was already gone with the football. One of the greatest running backs in the history of Grant High School, Bates had no need for size. He had speed.

“I wasn’t running anybody over,” Bates says now. “But I could basically come up to you full speed and be gone. For me, football was easy.”

He ran a 4.28-second 40-yard dash, which put him just shy of what’s accepted as the NFL’s record.

Born in Monroe, La., in 1952, Bates moved to Portland and said it was like a breath of fresh air. When he was young and living in the South, Bates and his family had to contend with severe racism. He remembers his family having to pack their own food whenever they went into town. There was no point in dealing with the restaurants. They wouldn’t be served.

“When we moved here, it was literally like coming to a new world,” he says. “We didn’t have much in the South.”

After making the journey across the country at age 9, Bates has fond memories of spending time at community centers around Portland.

He made the varsity track team at Grant High School his freshman year in 1967, his speed making him a coach’s dream. While at Grant, his crowning 60-yard dash time was 6.2 seconds, just .3 seconds shy of the world record. He was the city and state champion in that event.

He would have made varsity football freshman year had it not been for the overload of seniors on the team. His sophomore year, Bates earned his spot as starting varsity running back and held it until he graduated. He earned All-State honors his sophomore and junior years, and was honorable mention his senior year.

Bates pulled his hamstring at the first track meet of his sophomore year. For the first 90 yards of the 100-yard dash, “I was out,” Bates recalls. “I was way out.”

Bates was a few strides from the finish line when a sickening pop rang out. It was his leg.

“I call it my Joe Namath knee,” says Bates, who says his knee was operated on by the same surgeon who performed surgery on Namath, the legendary NFL quarterback. “It never really healed well enough for me to reach my zenith.”

Bates continued to smash records and humiliate defenders on the football field, but it wasn’t quite the same. “Pretty much everything I did, I basically did it on one leg,” he admits.

He recalls how college letters poured in his senior year, but due to his grades, he didn’t take any of the offers. He didn’t feel he was ready for Division I academics. Bates acknowledges that academics were not his strong suit in high school.

Instead, Bates began his collegiate years at Mount Hood Community College before moving on to play Division I at University of Texas at El Paso.

Next, Bates took his talents to the University of Hawaii where he studied business and ran track until 1976. But after tiring of the island lifestyle, he returned to Portland to work on the railroad.

Now Bates, 62, can often be found taking walks around Portland, at the gym or gardening. Bates has two children, seven grandchildren and a girlfriend of six years. He is retired from working at Consolidated Metals and on the railroad.

“All in all, I’m happy with my life. Everything worked out fine,” Bates says. “I feel blessed.”

Photo caption:Robert Bates remembers how he used his speed and quickness on the football field at Grant. He earned All-State honors in both football and track and field.

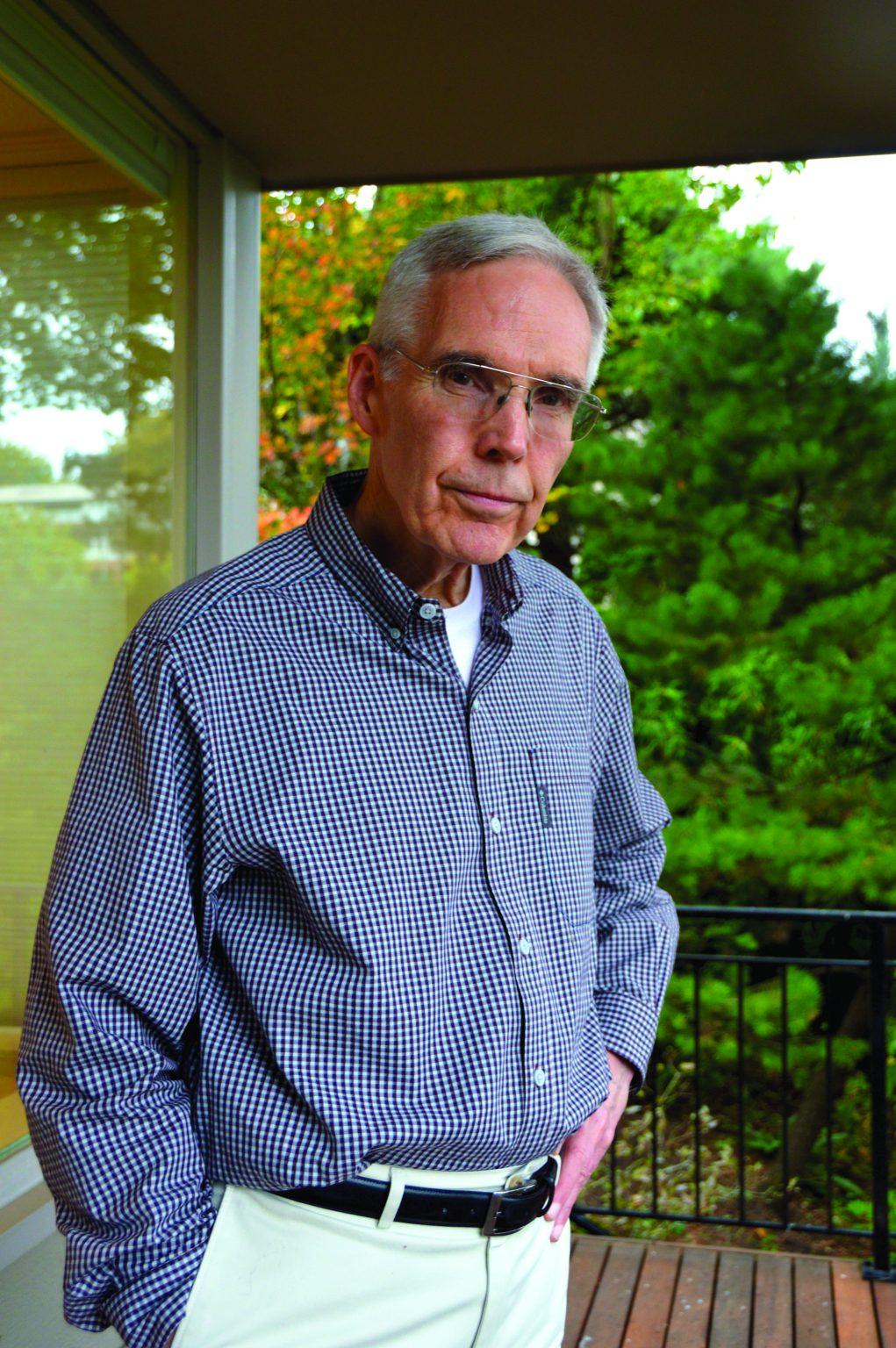

JOHN BAKKENSEN

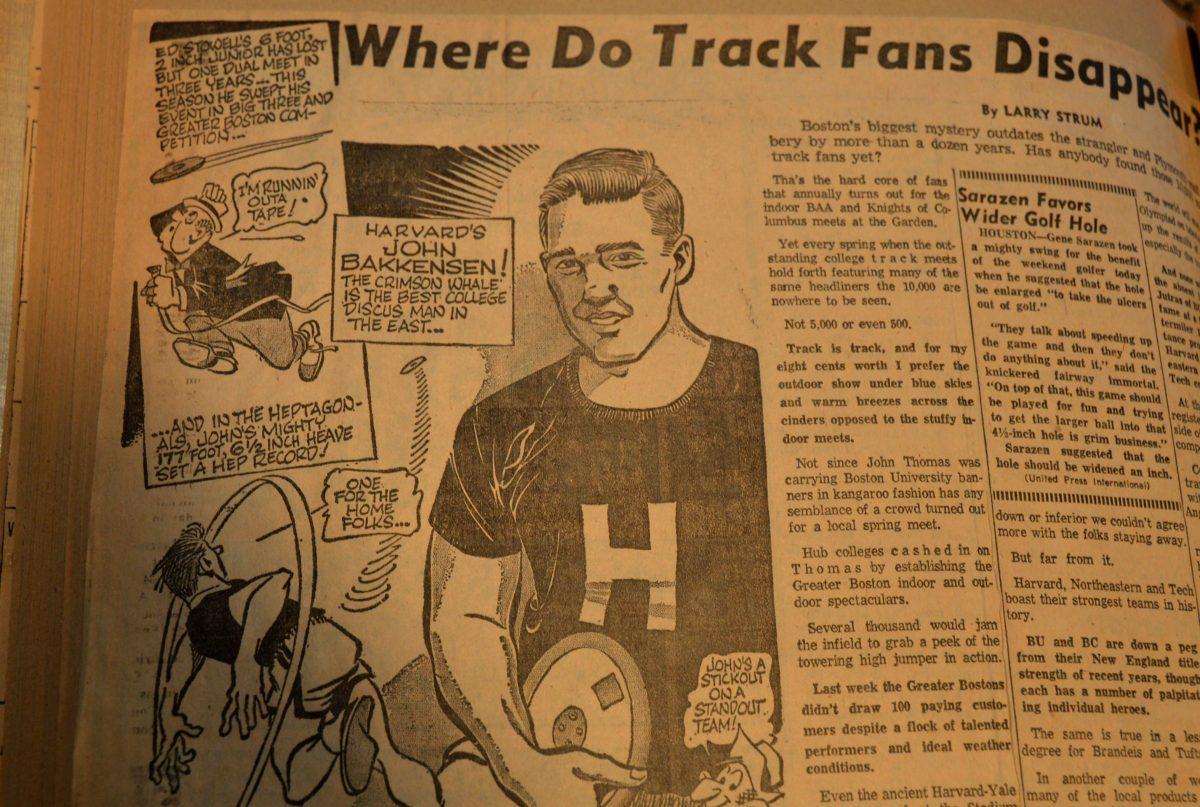

When John Bakkensen was a freshman in high school, he had no idea that throwing the discus could take him so far. The heavy metal disc changed his life.

“I was just looking for something to do in track,” he laughs. He attempted the high jump as well, but discus was his signature event.

Born in Pendleton, Bakkensen spent most of his childhood growing up in Portland after his family found its way over to the rainy city when he was 2. When it came time for high school, Bakkensen went with Grant, the largest school in the area. He didn’t go unrecognized.

Bakkensen was an outstanding discus thrower. By graduation he had won the Portland Interscholastic League title, the Oregon championship, and he had thrown the longest high school distance in Oregon’s recorded history at the time: 170 feet, 8 inches.

But he wasn’t finished. In 1961, Bakkensen’s talents and academic achievements took him to Harvard University where he continued to dominate in his event. “There’s an awful lot of technique involved,” Bakkensen says. “You just learn over time.”

While at Harvard, Bakkensen took first place all three times he threw discus at the Heptagonal Games, a conference championship that included the Ivy League schools, as well as Army and Navy. He won the IC4A championship twice in a row and left Harvard in 1965 as a nationally ranked thrower.

Next for Bakkensen was Stanford Law School, where he volunteered as a coach for the undergraduate track team. During his time there, he built a close relationship with Payton Jordan, the head coach of the United States track and field team for the 1968 Summer Olympics. That team won 24 medals – 12 of them gold. While coaching, Bakkensen continued to compete, throwing for Athens Athletic Club in Oakland.

He graduated from Stanford in 1968 and passed the bar exams in California and Oregon. He returned to Portland after graduating and worked as a lawyer for 32 years. He married and had three children, two of whom attended Yale University. His third child went to the University of Washington.

Bakkensen still threw the discus after becoming a lawyer, competing for Portland Track Club. In 1971, he hit his lifetime high, exceeding 201 feet. This was not far off the Olympic throwers’ distances at the time, but Bakkensen had other interests.

“I just didn’t have the time to dedicate to it,” he says.

He practiced law until 2000, when he became a commercial arbitrator for the Arbitration Service of Portland, and continued with that until early 2014. Now Bakkensen, 71, stays busy as a representative for various trusts.

He remains physically active by lifting weights and jogging seven days a week. He is looking forward to reuniting with old friends and teammates at the Hall of Fame induction ceremony. “It’s gonna be great to reconnect,” he says. ◊

Photo caption: John Bakkensen threw the discus at Grant High School and Harvard University. He won titles in the Portland Interscholastic League, the Oregon state championship and the Heptagonal Games in college.