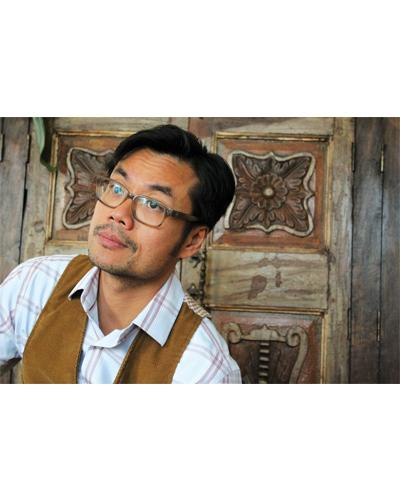

On a recent October morning, Vu Pham was dressed rather sharply. His short, dark hair was neatly kept and combed with a distinct part, and he wore a pressed white and pink broad plaid shirt, top button undone. A brown corduroy vest and dark grey slacks topped off his look.

His living room in Southeast Portland was cluttered, with grey Rubbermaid tubs in the center of the hardwood floor. Pham bustled around his house, preparing coffee and getting ready for the day. “Sorry for the mess,” he said, referring to the tubs. “They’re for craft service.”

He had an audition later that afternoon for a web series and said he planned on spending a majority of his day “tightening loose ends,” which really means returning cash to production companies he does craft service for. Later that night, he was at Lewis & Clark College to tend bar at a school event.

“It pays my bills,” Pham says simply. “My life is just a weird amalgam of all these different things that I try to keep as fluid as possible.”

Pham, who graduated from Grant in 1994, is 38. At best, his upbringing could be described as remarkably unusual; at worst, horrifically traumatizing. He characterizes himself as a “struggling, up-and-coming filmmaker,” and released his first short film in 2010.

He doesn’t exactly fit the description of “wildly successful.” He drives a modest white sedan, lives in a rented average-sized, three-bedroom home and balances several different jobs to keep financially afloat.

“Until I get that job that I want, which is a self-sufficient filmmaker, all other jobs are simply nothing more than varying means to get there,” he says.

From the beginning, Pham lived through what many would call hell. It’s been 32 years since he stepped onto American soil. His situation is much more enlightened than it was more than three decades ago. It’s also quite chaotic. But after years of struggle, Pham is beginning to figure it out.

“Fortune has smiled upon me,” he says. “I’m the luckiest guy I know. And I say that without blinking an eye.”

Pham spent most of 1981 on the move. Tension was heavy in Vietnam at the time, specifically the political situation. The aftermath of the Vietnam War had put the country in turmoil. Pham’s mother, who had spent of her life living with her father’s family, was drawn to the United States by the sway of democracy. “It was a political escape,” he says.

Pham, along with his mother and a half-uncle, clambered onto a rickety wooden fishing boat that was on its way to Thailand with other people from Vietnam.

Food and water were sparse. Passengers struggled with being packed on the ship and wrestled with the elements they faced while on the water.

“I remember the very palpable fear and panic and desperation that was experienced by a lot of people,” Pham recalls. “You’re throwing yourself into a type of situation that, you know, honestly, you would never think of doing.”

While on board, a passenger was bitten by a fish. Blood flowed from the wound. He remembers flare guns going off, as well as being sick for a vast majority of the ride. Then, a freight ship came. It was European, he recalls, and it was full of Caucasian men.

“Up to that point, I’d never seen what a white person looked like at all,” he says. “Strangely enough, I just remember thinking how tall their noses were – how slender and blonde, and tall and blue-eyed…and they helped us out.”

The freight ship crew gave them food. Pham recalls being “essentially hosed down” on deck. Eventually, the refugees reached Thailand. After stops in Malaysia and the Philippines, they finally arrived in the United States nearly a year later. Pham settled in Beaverton with his mother and the half-uncle.

They had almost nothing. Pham’s mother spent her days cleaning houses and attending classes at Portland Community College to learn English. Most of the money was sent back to family in Vietnam.

Shortly after moving to the states, Pham’s mother met her boyfriend, a fellow Vietnamese refugee. They dated for a while, but the relationship began to fall apart. Eventually, Pham’s mother cut ties.

The ex-boyfriend was also a refugee who apparently suffered from serious mental trauma after the Vietnamese-Cambodian War. When Pham was 8, the ex-boyfriend killed Pham’s mother.

“He robbed her of her right to a life,” Pham says. “When I think about the whole thing, the thing that makes me really sad is just knowing that this human being, my mother, who was a really brilliant woman and had so much heart and soul, did so much to make it over here and sacrificed so much to get to this country, only to basically be killed by some crazy person who couldn’t stand the idea of her being with some other man.”

Just two years after immigrating, Pham was left alone in a new country with a new guardian. He and his half-uncle bounced from home to home, never staying in one spot for more than a couple of years.

Pham never had a father figure growing up. His father, who was a military officer during the Vietnam War, was held as a political prisoner and met Pham once during his childhood. His uncle was the one constant and they were always on the move.

“Living with him wasn’t awesome,” Pham says, “because essentially, corporal punishment was a big deal. He was really kind of a maniac, and on top of that, he had all of these personal traumas and tragedies that he was going through. I grew up in a really abusive environment for a long time.”

Pham spent his first two years of high school at Madison. When he was 16, he ditched his uncle and started spending his nights on the streets, sleeping at bus shelters and the airport. In the mornings, Pham would find his way into the Madison locker rooms to quickly shower.

Living on the streets for three months, he spent his days in school, and his nights on the streets until a family in the community took him in.

“I’m in school,” he says. “But I’m outside even when I’m not in school. I certainly had moments where the situation felt hopeless.”

He was unconventional at Madison because “I felt really inadequate about myself,” Pham says. “I didn’t fit. I had such a strange social perspective and really, I just didn’t have a lot of social skills that kids my age already had.”

Pham was also disarmingly rebellious. During his time as sophomore class president, he simultaneously formed an underground paper that had “scathing criticisms of the school administration.” The paper, which went by the name “The Power of the People,” eventually found itself in the hands of the principal. Pham was expelled a few days later.

His junior year, he petitioned to go to Grant and won. Pham had to promise that he wouldn’t cause any trouble. He ran for student government and won. Despite his lack of social skills, he had a unique talent that allowed him to speak publicly.

“I think there was certainly a lot of things enjoyable about Grant,” he says. “I liked the diversity there. I thought it was cool.”

Pham kept his head down. He didn’t have many friends and admits he was mostly recognized as “a strange dude.” For the most part, Pham didn’t fit in at Grant, but that can be attributed to the fact that he didn’t know how. Given his background, he found it difficult to have the social life that most of his peers had developed.

“I was an awkward kid,” he says simply. “I don’t think a lot of people knew me.”

Pham’s life after high school grew increasingly complicated when he became a father and husband at age 18. His girlfriend from Madison was pregnant. It was a boy.

“I didn’t really have a solution,” he says. “I married a woman that I essentially wasn’t really in love with.”

He found jobs mostly in the restaurant or retail markets. Given the fact that he had become a father directly after high school, college wasn’t an option. “I was a working stiff,” he says. “I was just a guy trying to make ends meet.”

Later on in his marriage, it became increasingly evident to Pham that his mid 20s brought latent adolescence. He says he figuratively went through high school as an adult. He also became intensely self-aware of the state of his marriage.

“I decided that not being in love with somebody and marrying them seems like something that was unfair to both parties,” he says. “In simple terms: she deserved better.”

Toward the end of his marriage, Pham began to develop an acute interest in “beatnik” types. He started to experiment heavily with drugs.

“All of a sudden, I reverted to being a young person and exploring the world and you know, figuring things out,” he says. “Things that people had already kind of stumbled through.”

It was ultimately a process of delay. Nearly a decade removed from high school, Pham had essentially just finished growing up. He understood then, more than ever, what he wanted to do.He had an epiphany of sorts.

“It hit me like a diamond bullet,” he says.

Gone were the high school days: the social awkwardness; experimenting with psychedelic drugs; talking instead of doing. “I had work to do,” Pham says.

When he held a role as a featured background actor, he met Joe Jiang, who essentially did the same thing as Pham on set of the film. The first thing Jiang noticed was the way Pham spoke.

“Everything he says sounds like the most important thing in the world,” says Jiang. “And he’s not lying. He believes it.”

The two collaborated to create what would become Pham’s first official film, “Shining God,” which was released in 2010.

“When I first got in touch with him about working on projects, I was the one who was like, ‘Hey, you wanna be in my movie?’” says Jiang now. “But after chatting with him, he would just start talking about his projects and just somehow overpower whatever I was thinking about.”

Jiang and Pham were officially co-directors on the film. He was also working two jobs at the time.

“He’s like a machine,” says Jiang. “He’s a robot. He would work full on. Like, 20 hours a day if he had to get something done. When I first hung out with him, I think he was working at least 40 hours a week with his jobs. And then we were also doing the movie, so I took time off. If I’m doing a movie, I always have to take a couple of days off to shoot. He was working full time.”

Pham’s career began to generate more interest after Shining God. He was able to receive funds through grants and donations, but has paid for his last two films entirely out of pocket. Despite the cost, Pham is doing something that allows him to display his thoughts in a form of entertainment.

“I’ve always wanted to tell stories,” says Pham, who has made six other films. “The whole idea of all of this craziness is for me to get a feature film. An opportunity of that magnitude has the potential to make my career. It would change a lot of things.”

Today, Pham seems more relaxed on the set of his latest film, “The True Color of Hunger.” On a recent Monday in late September, Pham and his crew were shooting at a park in Southeast Portland.

The two leads in his film, Lindsae Klein and Matt DiBiasio, were preparing for the next shot in which they would walk across a pond on a narrow wooden bridge and onto a man-made dirt path. During rehearsals, Pham tailed them the entire time, instructing them on how to speak their lines and when to say them.

“Working with Vu is a little bit like a whirlwind,” says Klein, who has played a role in several of Pham’s films. “He has so much energy and focus and it’s just really contagious. I feel incredibly lucky to work with someone like Vu. He takes care of you.”

Pham officially classifies as a hybrid of sorts in the film industry: he writes, directs and produces films, but also dabbles in acting. His biggest role was in 2010, as a minor character in the film

“Extraordinary Measures,” which starred Harrison Ford and Brendan Fraser.

He wrapped up production on his latest film last month. It’s about 25 minutes long. Pham and his crew expect to completely finish it by the end of the calendar year.

Next year, he says he wants to move to Los Angeles and try to make it as a filmmaker and actor. “It’s gonna be tough,” says Jiang. “I know he’s gonna work his ass off, but it’s not easy to make it there. But I wouldn’t be surprised if Vu finds success.”

Whatever happens, he’s already made it, considering his upbringing. “Most people who’ve gone through what he has aren’t here,” says Pham’s girlfriend, Annette Pearson. “Vu is really successful. He’s doing what he wants to be doing. How many people can say that?”

Filmmaking for Pham has been an outlet. It doesn’t pay the bills; it doesn’t cover rent; it doesn’t pay for gas. Pham uses passion to do what he loves, and considering his situation now, he’s in a good place.

“I hear about lucky people all the time,” says Pham. “People win the lottery or do all these crazy things that others hear about. I don’t know those people. I do know me. I literally am the luckiest person I know. I survived on that boat. I lived through all this craziness with my uncle and my mother. To gather support for my art, and to have had it validated in that way? That’s huge.” ♦