Andre Broadous remembers being taken down in a professional Arena Football League game last spring. He felt pain in his knee, the same one that had been surgically repaired after he tore his medial collateral ligament years before.

The quarterback, who had graduated from Grant High School in 2008 and played Division I college football, knew the injury was serious but he kept playing in the game for the Tri-Cities Fever. The next day, he woke up unable to walk. He’d torn his MCL again.

“It definitely was hard for me because after that I pretty much knew that I would be done with football,” says Broadous, who is back in Portland. “I knew that day was gonna come, but I had my degree and I was prepared.”

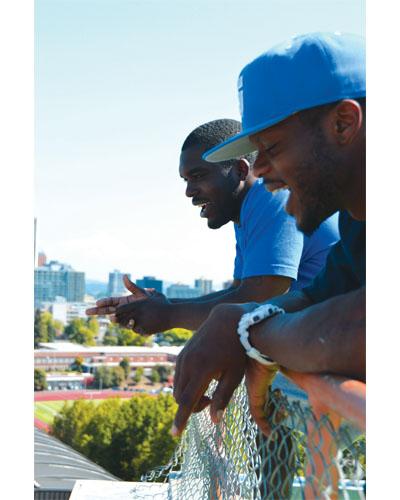

His childhood friend and former Grant teammate Alex Melson had recently finished a standout collegiate football career at Western Oregon University. He was back in Portland applying his degree in exercise science at various gyms around the city as an athletic personal trainer.

“College football was everything I expected it to be,” Melson says. “It’s just exciting. You’ve got a lot more guys that are just as enthused to play the game as you are. The competition is harder, the dedication is stronger and the all around game is just faster and better.”

As Class of 2008 alumni, Broadous and Melson left behind an era of impressive records and strong playoff runs, a period considered to be a golden age of Grant athletics. Now, six years later, the two are back at a time that sees Grant football at a crossroads. Last year’s varsity team won just two games all season. The team hasn’t advanced past the first round of playoffs since 2011.

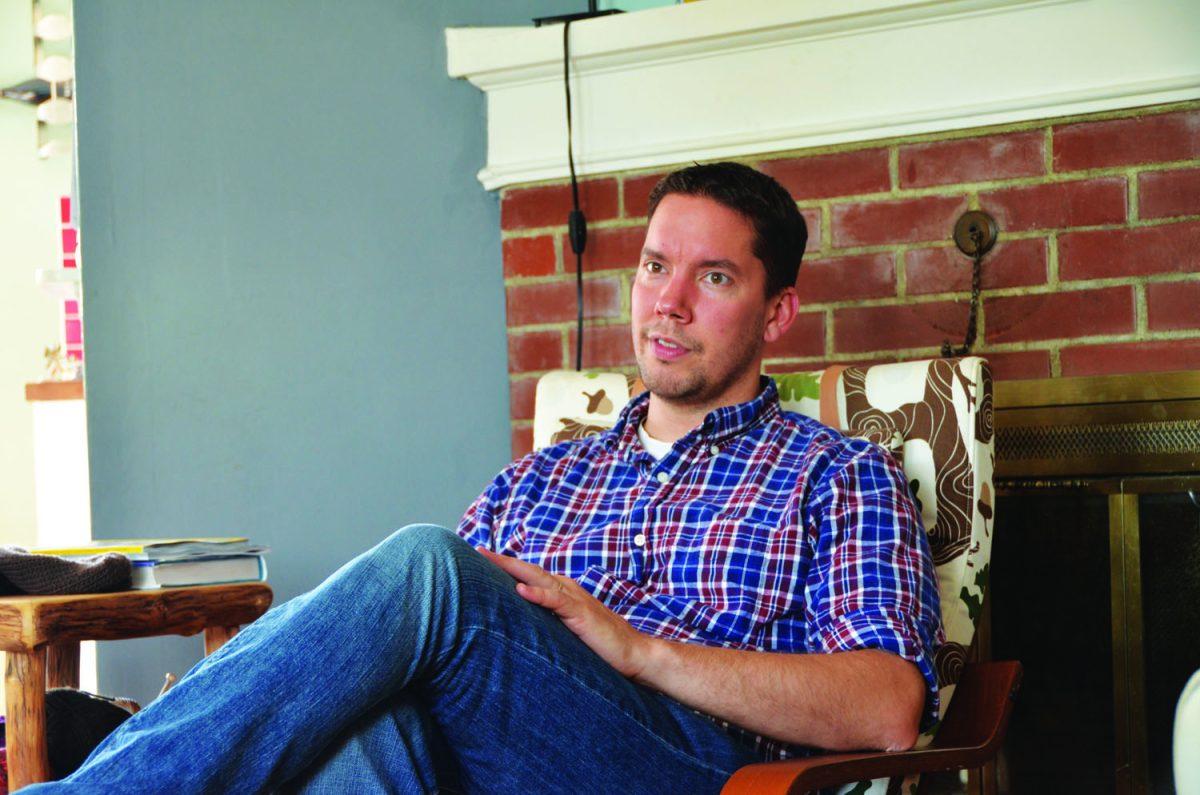

Now, Head Coach Diallo Lewis has brought in two of the players who starred here to help develop the program. They’ll work as assistant coaches for the freshmen team, as Lewis wants their high-level knowledge, experience and devotion to help set a sturdy foundation for the Grant program’s future.

“They understand the system that we’re running,” says Lewis. “They are committed to building a solid program.”

For their parts, Melson and Broadous don’t want to let their old coach down. “I just wanna show them how to play the game right,” says Melson, 24. “Not as far as Xs and Os, but the passion and the dedication and everything it takes to get to the next level.”

“My main goal is to get them to be better overall people rather than just good football players,” Broadous says of the freshman he’ll be coaching.

Broadous is scheduled to be inducted into the Grant Sports Hall of Fame in October. He spent his collegiate career at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, leading his team to win the Big Sky conference in his final season. And his career didn’t stop there. Broadous played professionally for Tri-Cities Fever until the injury.

Karl Acker, Grant’s freshmen football coach, couldn’t be happier to see the two stars return. “They’re both solid athletes and scholars and role models for our young guys to follow,” says Acker. “Having them as a part of the team is definitely going to benefit us.”

The story of Broadous and Melson is much deeper than just football. They’ve known each other for two decades and they consider themselves brothers.

Broadous was born and raised in Northeast Portland. Melson was born in Heidelberg, Germany to a mother stationed with the military overseas. But he came to Portland within a few months. The boys grew up side by side, understandably, since their fathers were childhood friends.

Together, they moved up through the ranks of Woodlawn Elementary. During their childhoods, it would have been difficult to find them not playing a sport.

With separated parents, Broadous received his support from two different households. However, he was unfazed, and had a large church family to fall back on.

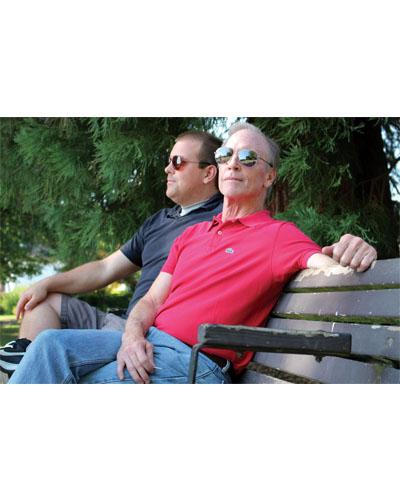

James Broadous has fond memories of his son’s earliest athletic endeavors. Before he was old enough to play flag football, Broadous was serious about joining a team. His dad pulled some strings to get his son a position, and before he knew it, the six-year-old Broadous was playing organized football alongside nine-year-olds kids, his dad says.

James Broadous watched as his son outworked and outsmarted the older kids on the field, unconcerned by his less-developed body. At home, young Broadous would sketch play diagrams on paper. His family knew at this point that he was destined to go far as an athlete.

Around age 10, Broadous worked extra time into his schedule for sports. He woke up before school every morning to practice.

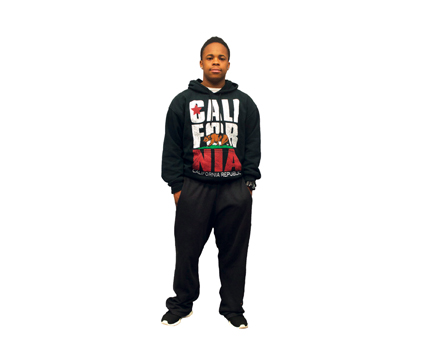

When Broadous’ friend Melson wasn’t playing a sport, he was likely nurturing his fondness of music. He spent a lot of time playing the trombone and the piano. Regardless, sports were his life from a young age.

“Once I started playing sports, I never really turned back,” Melson says.

He remembers becoming a year-round athlete as early as second grade, getting involved in every sport available to him, namely football, basketball and baseball. “Me and Broadous have been playing together since we were young pups,” Melson says.

It was through baseball that the two first established a relationship with Lewis. He first met the boys during the spring of their eighth-grade year after a baseball game. Melson and Broadous went up to introduce themselves.

“They were confident young men who were committed to working and bringing their best,” Lewis says. “They were competitive. They were solid students and their parents were very supportive.”

The next few months passed quickly, and before they knew it, Broadous and Melson were out on the field trying out for Grant football. The freshman group, with Broadous and Melson as standout players, went undefeated in their first season.

The following year, the duo made their debut on varsity with Broadous starting as a sophomore and Melson playing linebacker and running back. The three years that followed were outstanding, they said. With Broadous and Melson as key players, the Grant squad went through each year with near flawless records, pushing far into the playoffs. They made it to the quarterfinals twice and the semifinals once.

“I feel like we had a good enough team but we didn’t get it done,” says Melson, mentioning how they only lost six games throughout his four years at Grant. He was selected First Team All-Conference, Second Team All-State, and was the PIL Defensive Player of the Year.

“I feel like we had a good enough team but we didn’t get it done,” says Melson, mentioning how they only lost six games throughout his four years at Grant. He was selected First Team All-Conference, Second Team All-State, and was the PIL Defensive Player of the Year.

Senior year, they were city champions for the second year and the team was gunning for a state championship. But Sheldon High School cut their nearly undefeated season just one game short, knocking them out of the state semifinals.

Broadous, who earned Oregon Offensive Player of the Year twice in a row, had led the Generals the farthest any Grant football team had gone in the playoffs since 1964. He was also part of the basketball team that won a state championship months later and both played baseball in the spring.

While juggling sports, Broadous and Melson still saw the value in education throughout their academic careers and maintained respectable GPAs. Their work ethic put them in good shape for when college rolled around.

Broadous has watched many talented athletes fall through the cracks – a consequence of not being well rounded. He sees the value in education and realized early on he couldn’t just be an athlete. “I had to focus on academics, as well,” he says.

For Melson, going with Western Oregon University was an easy choice; he appreciated the location and the scholarship offer.

Broadous had offers from Arizona State, Portland State, Oregon State and California Polytechnic. During his senior year, he flew to California to see the campus of California Polytechnic. He quickly fell in love with the atmosphere. Looking at a full ride scholarship, he decided to go with the Division I school.

Both Melson and Broadous spent their first college football season as redshirts, meaning they worked out with the team but saved a year of eligibility. Melson played through his career at Western as a standout defensive player. At the same time, he still worked hard in the classroom, and earned his degree in exercise science, something he had keen interest in.

Broadous started games here and there during his early seasons at college. But in his final two years of college football, he was the starting quarterback. In 2012, during his final season in college, he was named Cal Poly’s offensive most valuable player and the team won the Big Sky conference. That game was particularly special to the Broadous family because it followed a significant injury.

Two weeks before the conference game in November, Andre Broadous suffered a neck injury. His doctor said he would not play. His season was over.

But Broadous made a quick recovery. He went out and helped win the conference title with his team. “Now that was a special moment, a crowning moment,” says his father, who rarely missed Broadous’ college games.

Once Alex Melson finished his final football season and graduated from Western Oregon, he found a way to put his exercise science degree to use. He returned to Portland to work at various gyms around the city as an athletic personal trainer.

“I’m just really into exercise science, training the body, eating right,” Melson says. “I’m always in the books looking to get new information and knowledge on training.”

Broadous however, wasn’t ready to hang up the helmet. He received various invitations to showcases and NFL tryouts, but nothing was guaranteed. That was, until he received an offer to play professionally. With his college career behind him, he had some decisions to make.

An offer came in from the Tri-Cities Fever, an Arena Football League team. Broadous had a difficult time deciding if he wanted to leave school early to play. He would still graduate, but he wouldn’t get to walk the stage. His father brought words of encouragement.

He told his son: “This is something you’ve always wanted to do, to have an opportunity to play professional football and get paid, so this is great, this is the dream. Not everybody gets to play college ball, so getting to play at another level, that’s special.”

Broadous decided to go with the guaranteed money and headed up to Washington to try his hand at arena football. “It’s a lot faster and a lot more action packed,” Broadous says. “Everything is quicker for the quarterback. It’s just a different game. It was a good experience.”

Last spring, it all came to an abrupt end with the tearing of his MCL for the second time.

Now, Broadous and Melson are back at Grant coaching the game they love. Broadous will be helping coach Acker with the offense and Melson with the defense.

Lewis says he thinks his former stars will help Grant’s football program move forward faster. “It’s really important that kids come in and have a great experience,” he says, adding that a positive freshman year instills new players with “great interest, commitment and excitement for the JV and varsity seasons.”

Acker couldn’t agree more. Each year, the freshman team has kids who have never played before. “If they have a bad experience, they could be soured on the sport for the rest of their lives,” he says.

Having an ex-professional and an ex-collegiate football player on the field gets kids more excited about football. “It’s very important to have a staff in place that really understand the growth of the 14-year-old kids and help them transition into high school so they can more than just be good students,” Acker says.

Broadous and Melson say they are ready to step up to the challenge, and it won’t just be about the football. Broadous has already latched on to Acker’s philosophy of self-improvement for his players, and is serious about building character and life skills. Melson feels a personal responsibility.

“There was always a coach there that was always checking up on me in school, and those coaches were one of the reasons I was successful,” Melson says. “I feel like I can give back by doing the same things for the freshmen that are around now.”

Broadous will also receive his license to be a real estate agent in October and he’s tried his hand at developing mobile phone applications.

Melson has a creative side and though he stopped playing instruments once he got serious about sports, he is now getting back into music. He has a small studio in his house and is producing hip-hop beats. Down the road, he’ll likely finish his education and work as a physical therapist.

Lewis knows both young men may eventually be pulled away from the program by other opportunities, but he sees the potential to be great coaches. “They are now young men with degrees. They’re professionals who are looking to inspire and motivate. They’re just really good guys, quality guys, and I think they’ll be great for Grant.” ◊