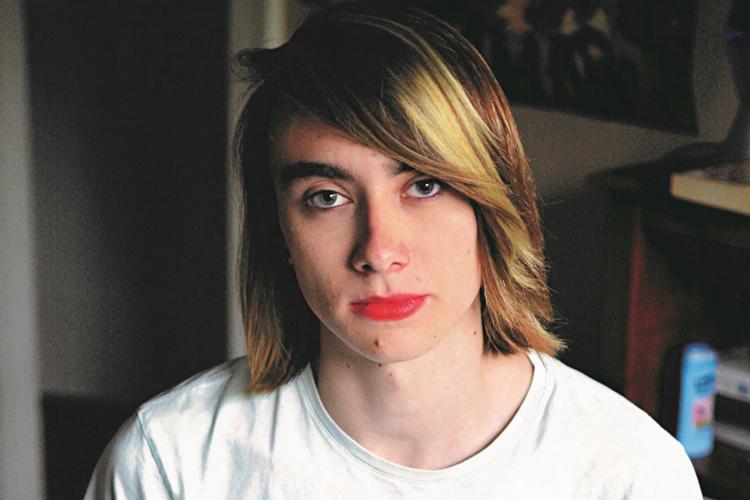

It’s a Monday morning and Grant High School student Aaron Karson is late for class. He runs downstairs and yanks his backpack from its resting place. Instead of bothering with breakfast, he scrambles for a pill bottle marked with a Vyvanse logo. He dumps a little blue and white capsule into his palm, tosses it into his mouth and swallows as he sprints out of his house.

The effects come quickly. In English class, Karson finishes a written essay at the same time as everyone else, managing to sustain his attention when he otherwise couldn’t have.

“What Vyvanse does for me is it gives me the power to focus on school,” he says.

But as lunchtime nears, so do the side effects of the medication. Karson isn’t at all hungry or thirsty. “Throughout the day, I have to consciously think: ‘It’s been a few hours since I’ve eaten anything. I’m getting kind of bitchy. I should probably go eat something,’” he says.

“Or, ‘My mouth is dry and I’m dehydrated. I really need to drink a glass of water right now.’”

He doesn’t emotionally engage with his friends as much, missing out on some of their interactions. And when it starts to wear off, there’s a come down. “You feel kind of drained. You feel a little bit more gray and kind of ghostly and hollow,” he says. “I’m definitely a lot more irritable during the come down. There’s not much more I want to do other than go home and not think about anything for the next 12 hours until I have to get up and do it all again.”

The drug allows him to work, but at an almost robotic level. And Karson’s not alone. Doctors put thousands of teens across the country on medications like Vyvanse, Adderall or any number of the types of pills used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. When those teens come to school, there are benefits. But are we ignoring the impact of the side effects on students?

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration lists the most common side effects as staggering, trouble sleeping, headache, stomach ache, weight loss, dry mouth, fast heartbeat, decreased appetite, nervousness, mood swings and dizziness. Medical experts say the decisions they make are made in consultation with patients and their parents.

Still, doctors acknowledge that there’s a tradeoff.

Dr. Mary Lee Baker, a Northeast Portland pediatrician, says she sees many kids who feel that Adderall takes away their personality. “If that’s a big negative for people, that’s when you say: ‘OK, we need to try something different,’” she says. “Everything’s got its pluses and minuses and that’s what we’re trying to balance. Most parents are skeptical of it. But when they see the benefits, then they’re fine with it.”

Karson recalls how the pressure of school and other issues caused his life to spiral before he was diagnosed with ADHD. Often during his junior year, he would sit down at his desk after school and scatter his work in front of him. Met by a familiar flood of frustration, fear and self-doubt, he’d remain in that position until late into the night.

He’d stare blankly at the clutter until he would finally give himself over to his drug of choice, usually Oxycontin – an addictive, narcotic painkiller. Quickly immersed in a foggy state, he was able to cope with his emotions.

Karson says he also drank alcohol and self-harmed as a way to feel something else as intensely as he felt his frustration.

And the classes he was taking had grown tougher. His grades slipped and tension increased with his parents. He tried having parental oversight while he studied. He kept a planner, turned off his phone and the Internet. The family hired tutors and set up a reward system. “I just tried a lot of different study habits and kinds of ways to manage work,” he recalls. “They all just didn’t work well enough.”

Once he started taking the medication, tension with his parents decreased and Karson says his depression was alleviated. His grades went from mostly failing to As, Bs and Cs in just one semester. He says he’ll live with the side effects, given what happens when he is medicated. “The grades don’t negate the bad parts of it, but they do compensate them. I’ll still continue to do it because of the obvious and important results,” he says.

“If you have ADHD, it’s like living in a rain of post-it notes, and every single one has a piece of information on it.” – Joe Kilty

Tamara Anderson is a special education teacher in the Parkrose School District. She works with students whose ADHD is too severe for them to function in a regular classroom with standard curriculum. She says the kids can be intelligent but unable to complete their studies, causing a level of friction.

“A lot of ADHD kids have high IQs, so their potential for learning is high,” Anderson says. “But the product that they’re putting out in school is low. It’s common for them to be really smart, but not able to finish anything. There’s a lot of frustration for people who have ADHD because you’re trying to do well in school and if you don’t have a good handle on it, it can be very frustrating.”

According to a Centers for Disease Control survey, one in five high school boys in the United States and one in 11 high school girls were diagnosed with ADHD in 2011. Diagnosed teens can be treated with a stimulant, sometimes made with amphetamines.

“Medications are often used when function is impaired to the point where someone cannot be successful at school or work even with good coping mechanisms,” says Heather M. Penny, a Northeast Portland family doctor.

According to the 2011 survey – the most recent one done by the CDC – more than 65 percent of Oregon youth with ADHD made the decision to take drugs.

Adderall is the most popular of the amphetamine medications. It’s also one of the most potent so it’s usually prescribed early on, then changed depending on how the patient reacts. People with attention deficit disorders have neurosystems that transmit signals somewhat differently. The affliction makes focusing on one task at a time – like organizing, listening to instructions or prioritizing – more difficult.

Doctors say Adderall can be prescribed to kids as young as age 3 to stimulate the nervous system.

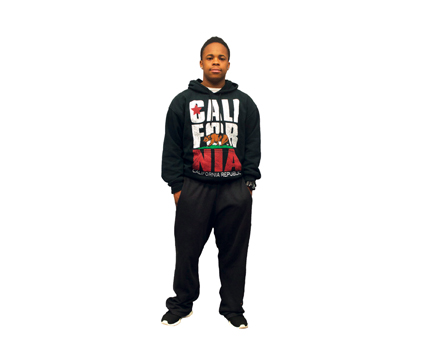

For senior Joe Kilty, finding the right kind of medication was key. He takes Concerta, a drug that helps him stay organized and on task. Its scientific name is methylphenidate and it’s known as one of the more effective ADHD drugs.

“If you have ADHD, it’s like living in a rain of post-it notes, and every single one has a piece of information on it,” says Kilty, who was diagnosed in third grade.

“Someone without ADHD has a big, clean whiteboard. A lot of their thoughts, the little ones, can just kind of get pushed to the side. They can get written in the corner, and only the really important ones get written in the middle. For someone with ADHD, every single thought they think has to be written on the whiteboard in big, capital letters, underlined a lot of times. So you pay attention to everything. It’s not inattention, it’s paying attention to too much.”

He had tried Adderall, but the negatives were enough to make him switch medications. “The side effects outweighed the actual advantage of taking the medication,” he recalls. “It wasn’t worth it to take the medication anymore because it was hurting my body.”

Kilty switched to Vyvanse, but he felt it was worse. In the summertime, he takes the Concerta about two or three times a week. It allows him to do things that require focus, like watching his sister or cleaning the house. During the school year, he takes it daily.

“It doesn’t change how I feel. It changes how I act,” he says. “I would say I’m a lot less impulsive. That’s why I started taking it in the first place. I think about what I say a lot more and that I’m able to control my energy.”

But ADHD medications present some risk and can be addictive. Medical experts say parents and family should be on the lookout for the potential for abuse and dependency.

Karson takes the medicine weekly during the summer. “I thought that I just basically wouldn’t do it,” he says. “But some days, it’s been much easier and sometimes even a preferable option to make myself feel just flat and focus on something even if it’s stupid than kind of feel my emotions. It’s a choice between knowing I could be hopped up on amphetamines and not have to deal with whatever it is that is happening.”

Grant High administrators say regardless of whether a student has ADHD or not, making sure they can get the best education possible is the point.

“Our goal is to make sure that teachers are working with families and students to make sure that we’re providing instruction and opportunity for every kid to be successful,” says Principal Carol Campbell. “And if that means that we have to accommodate or make some adjustments to what we’re doing, then yeah, we want to do that.”

Grant English teacher Mary Rodeback sets up her own strategies to help kids with ADHD. “We try to have kids get up and move around a couple of times during the class, and we never spend the class period doing just one thing or even just two things,” she says.

Grant English teacher Mary Rodeback sets up her own strategies to help kids with ADHD. “We try to have kids get up and move around a couple of times during the class, and we never spend the class period doing just one thing or even just two things,” she says.

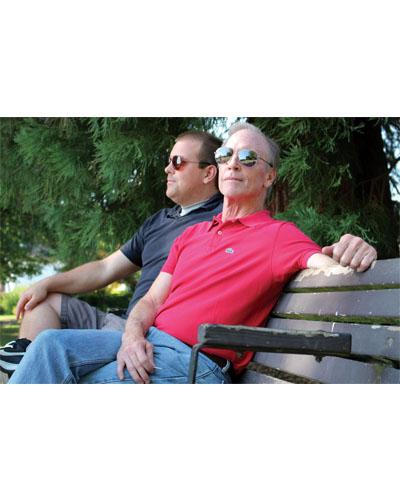

History teacher David Lickey struggles with ADHD himself. He teaches a lecture-style class and he knows that focusing for long periods of time can be a struggle for kids, especially those with attention deficit disorders. His strategy is to use engaging material.

Lickey has never been formally diagnosed or prescribed a medicine, but he’s sure he has it. “Things that are boring to me I just can’t concentrate on. I want to. I know it’s important, but I just can’t,” he says.

He says he’s able to focus and be an effective teacher because he exercises. Studies back Lickey’s assertion – physical fitness plays a big role in someone’s ability to focus.

Anderson of the Parkrose district agrees. “Exercise is huge,” she says. “Having the endorphins in your brain just can help you have a more positive outlook on life in general.”

Lickey thinks allowing students to get more exercise in school, as well as providing a wider variety of classes, would allow kids to succeed more.

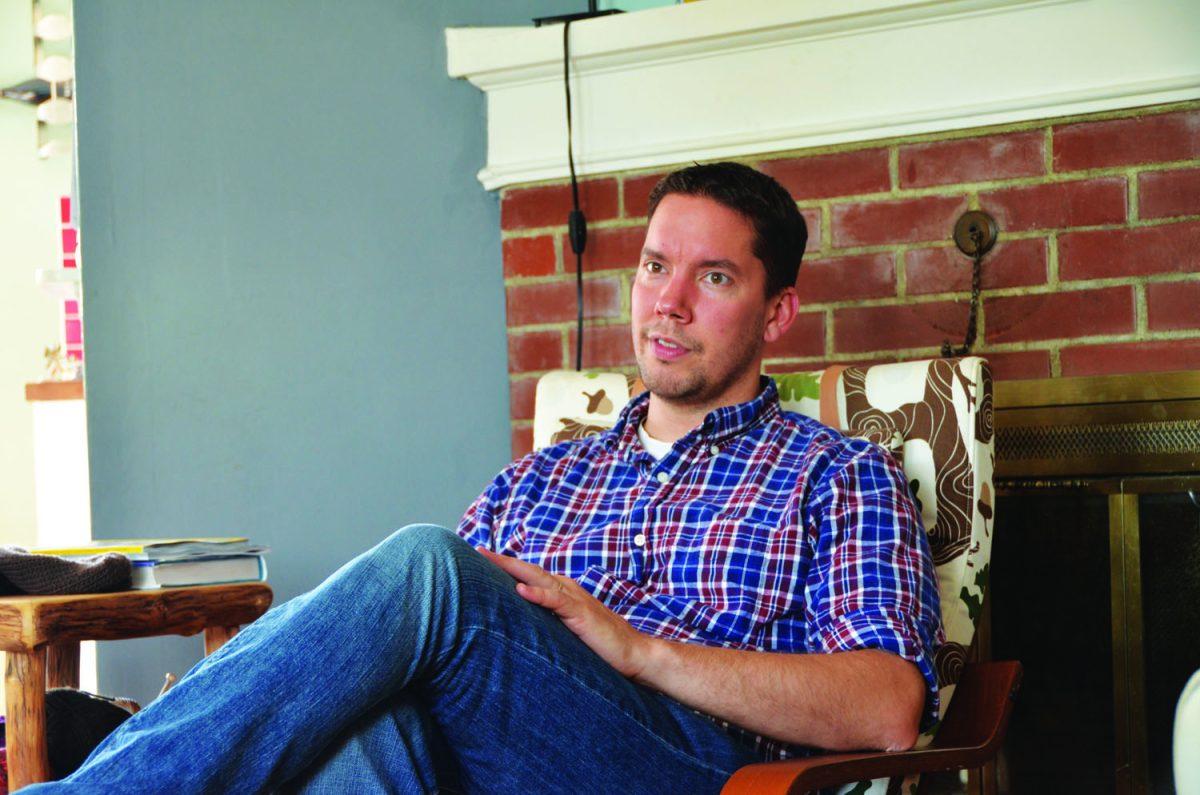

But the organizing, planning, and focus that is so frustrating for kids with ADHD doesn’t end after school. Most jobs require similar skills and attention. As a result, many adults must continue taking the medication because of the requirements of their job, still enduring the same side effects.

The brains of people with ADHD are different, Lickey says, and that shouldn’t necessarily be seen as a bad thing. “I’m along that spectrum, and while I’m highly distractible, I also have a creative mind,” he says.

Susan Bettis Smith, a Portland counselor who works with adults who have ADHD, sees this in her work. “So many people tell stories about how much they enjoy their ADHD,” she says. “It’s fun and it’s quirky and it’s imaginative.”

Smith thinks people with ADHD would excel at flexible jobs where you can jump from task to task; although she says that doesn’t always need to be the case. She’s seen that many of her clients have an exceptional ability to hyperfocus on things they’re interested in. “People say, ‘I couldn’t stay focused making my kid’s lunch, but then I spend six hours working on my written projects,’” she says. “With ADHD, a lot of times finding your bliss is what helps you to focus.”

In high school, Lickey could hardly focus on schoolwork. But, he says, “I would make these incredible models that would take hour and hours and hours.”

Now in his down time, Lickey makes models or furniture frequently. “Once I get going, I can dink around with intense concentration for 12 hours at a stretch,” he says. “I’m capable of maintaining very focused. But only when it’s something that really grabs my attention.”

The classroom can be modeled to create those kinds of opportunities. Doing things in class involving movement might be necessary for kids with ADHD, but it helps all students. “Taking those kinds of breaks and doing something physical actually helps to cement those ideas in our heads,” says Rodeback.

Karson hopes he won’t have to continue with the drug. But he wants to go into the bioengineering field. “With every job, there will be some paperwork,” he says. “Right now, that’s something that I would need medication to get done in a timely manner.”

Experts conclude that if people with ADHD are interested in something that requires a lot of focus, medication may still be a necessity.

Joe Kilty aspires to become a lawyer. He thinks this means he’ll have to take the medicine for the rest of his life. “That’s something where you need to be focused,” he says. “And I feel like it would allow me to succeed a little bit more.” ◊