On a Tuesday night in late January, the Grant High School boy’s basketball team took on the Sheldon Irish in the Grant gym. In an attempt to attract more students to what has been a sparse cheering section, the athletic department announced that all students had to do was wear Grant clothing and they would be admitted into the game for free.

As the varsity game tipped off, the visiting team from nearly 115 miles away was still backed by more student fans. Playing from behind the entire game, the Generals were never able to overcome the deficit on their home court, eventually losing by three points. Then 13-3 and ranked third in the state, it was only Grant’s second loss to an Oregon opponent.

Head basketball coach Paul Kelly, a 1990 Grant graduate, wonders why his team is not getting the attention that it deserves. “I look up there most of the time and it’s parents and maybe a few basketball junkies,” he says. “We are not getting any of the student body at all.”

Senior Jaalen Johnson has played the whole season wondering if his peers have even realized how successful the team has been. “We want this team to be something the whole school can get excited about,” says Johnson, who plays guard. “But right now it seems like nobody can take the time out of their day to support us.”

The lack of support is reflective of a dramatic decline in school spirit across the board. Five years ago, few would question Grant’s role as an elite school in the state that had both athletic success and fan participation.

But while the talent today hasn’t wavered, the fans haven’t exactly been lining up before games for a seat. There are a myriad of possible explanations for the decline in fan participation. Everyone from students to faculty to coaches has ideas of what has happened, how to restore the rich fan tradition and what it means to be a General.

Freshmen football and varsity track coach since 2006, Karl Acker says: “I don’t think that students now carry school spirit as a priority. When we were coming up, you take pride in your school, you take pride in your colors.”

Marty Williams graduated from Grant in 1998. He’s been a Grant employee for seven years and is currently an assistant football coach. “How many kids can actually say, ‘Man, I love Grant’? There was a camaraderie when I went to school, whatever you played, whoever you played, it was blue and gray all day.”

Grant’s past is filled with images of remarkable community support. For decades, Grant athletics has brought people together from across the city to witness some of the state’s most elite talent. Kelly recalls his first memories of Grant basketball, beginning in eighth grade. In 1985, he was captivated by a four-overtime home game between Grant and Wilson. “It was filled to capacity,” he recalls. “Both baselines were covered and the fire marshal had to stop letting people in.”

Kelly appreciates everything Grant basketball has offered him, especially as he was growing up. The Grant gym allowed Kelly to familiarize himself with the up and coming local players and experience an electric environment. He recalls watching “the best athletes that I have ever seen playing in the same gym that we are playing in today.”

Vice Principal Curtis Wilson, in his fifth year at Grant, is a graduate of Roosevelt High School. He puts it simply: “Years ago, Grant was the place to be for basketball.”

Kevin Alvord has taught at Grant for 12 years and has coached junior varsity basketball and freshmen soccer. He says he saw lots more fan involvement in previous years in all sports. He remembers the baseball season in 2005. “Students used get the BBQ going and drag out like five couches and put them along the field. Now, you’re lucky to find anybody but the parents out there,” he says.

In 2006, Grant played a crucial football game against Lincoln on the other school’s home turf. The top two spots in the conference were secured and the winner would determine the PIL champion. “Everybody from the community was there,” says Williams.

Thousands of people filled the Lincoln stands, surrounded the track and packed the portable bleachers set up behind the opposite sideline. Grant math teacher Jim Tucker was keeping track of the stats that night. He remembers “a wave of sound wafting across the field.”

Acker started coaching with Grant Youth Football after moving to Portland in 1990. In 2006, he became the freshmen football coach and was soon added to the track coaching staff. When his son, Kenneth, graduated and went on to play football at Southern Methodist University, the coach saw what he believes was a “new era” and a huge drop-off in fan participation.

“It was almost a rebellion. It was like this negative cloud came over the students,” he says.

Acker remembers asking a student to join the rally bus, headed down to Roseburg for a playoff football game in 2010, and the student told him, “Why would I go? They’re not going to win anyway.”

In Acker’s eyes, the class that preceded his son’s ushered in a new culture at Grant, and “they didn’t carry the torch.”

Students, teachers and coaches all have different theories about why the “new era” has taken Grant by storm. Members of the Grant staff, who have been around Grant athletics for years, believe the height of technology has transformed the fan experience.

“With today’s generation, guys would much rather be sitting at home on Facebook, Twitter or video games than sitting in a gym,” Acker says.

Kelly says the shift in interest starts from a young age. “They’re not in the parks. They’re not in the playground meeting new people. Kids stay to themselves more.”

Social media has also changed the way students gather and socialize. “Everyone used to go to the game to find out what was happening afterwards, but now everyone’s tweeting, posting and texting about it,” Kelly says. “Even at the game, half the crowd is on their phone.”

The behavior of today’s generation has had a significant impact on how students communicate, but changes within the school have also hurt fan numbers. A couple years back, the administration, in collaboration with students, used to conduct a pep assembly every three to five weeks. This year the school has had one.

Senior Giovanna Bishop says pep assemblies play a huge role in getting students excited to come to games. “They are the best memories I have of freshman year,” she says.

Co-athletic Director Matt Kabza admits: “Pep assemblies allow students to get to know the personalities of the athletes and coaches.”

But his colleague and co-athletic director Diallo Lewis says assemblies aren’t as easy to put on as they might seem. “The assemblies have to be well planned,” Lewis says. “Students have to leave with a sense of community and pride. That’s what brings students back to the gym.”

Wilson says assemblies are very stressful for the administration but they are also effective because “it puts whoever the assembly is about at the forefront of the school.”

Budget cuts have stretched school resources thin, eliminating the activities director position and contributing to the difficulty of piecing together creative ways to attract and unite students on a regular basis. Grant is in a transitional period. A new principal and a new vice principal within the past three years, two new athletic directors and a reshuffling of the student council. “It’s going to take some time to make a lot of subtle changes,” says Wilson.

Some students say they feel like the new Grant administration has implemented stricter policies at school-wide events. Senior Aidan Silvis says: “A lot of kids don’t want to come to games if they feel like they are being watched all the time.”

Some students say they feel like the new Grant administration has implemented stricter policies at school-wide events. Senior Aidan Silvis says: “A lot of kids don’t want to come to games if they feel like they are being watched all the time.”

Senior Cameron Kokes believes he has a high level of pride for Grant and loves the “energy and excitement” of school events. But he says “some kids want to feel like they are escaping school on a Friday night. Coming back to a school-run event makes some people feel trapped.”

Alvord sees numerous examples of a stricter administration leading to less student participation. For example, Toga Day used to be “kind of insane around here, in both good and bad ways.” He says he appreciated the school’s effort to crack down on the alcohol use by students that was associated with the event.

But “it has also made overall involvement really taper off,” Alvord says.

The way the long-standing tradition has evolved is another example of students getting “sat on more, not allowed to just go wild,” he says, and in turn more students shy away from school activities.

Grant students ultimately make the decision to attend or not attend events. Tucker says: “There will always be a part of the student body that athletics is just not something they desire. But when our gym looks empty, we don’t have enough of the student body saying it’s cool to go to the games.”

Senior Chance Whitehurst says the only time he goes to a game is if a friend is playing. Senior Adam Lawler says he’s simply not that interested in the sports that tend to draw the biggest crowds.

Will Stevenson, a senior who plays soccer, says: “It’s hard for me and my friends to get involved in the enthusiasm. I usually just don’t feel like going.”

Kelly says he’s disappointed to not see other sports teams regularly cheering in the stands. “I don’t see the student section laced with football players cheering on their classmates. If the football guys are not in the stands being rowdy, blowing steam, then who else is?”

Alvord says club sports that ask athletes to participate year round have had an impact. “With the specialization of sports, athletes that are so focused on their own sport don’t have time to make it to others,” he says.

The recent decline in fan participation doesn’t have to be a negative reflection of the school as a whole. Both coaches and student athletes suggest that the school’s well roundedness and the emphasis the staff places on a range of extracurricular activities may have taken away from the pool of sports fans.

Senior standout runner and soccer player Parkes Kendrick says sports aren’t the only focus. “It seems like Grant really treads lightly on trying to represent different student activities, whether it’s art, music or sports,” she says. “I think they are uncomfortable trying to promote just athletics too much.”

With the break up of the original Portland Interscholastic League, cross-town rivalries have pretty much been lost. “It separates the community,” Williams says.

Kelly remembers Portland basketball was extremely competitive. Every year from 1985 to 1990, a PIL school either won or was a finalist in the state basketball championship. “From a basketball standpoint, representing your school was huge because of the competition level around the city.”

As the athletic supervisor, Wilson sees this in practice. “There are schools that come here that students have never heard of. Grant doesn’t have a tradition against these schools,” he says.

The number one cause of the decline of school spirit at Grant in Alvord’s eyes is that there are very few in-school coaches to initiate a lot of excitement around their particular sport. When Alvord was in school at Madison, every coach was a school staff member. “They were legends and they built it up,” he says.

This year is the first in the history of Grant when not a single basketball coach at any level – girl’s or boy’s – works in the school.

“Coaches inside the school drive a lot energy, they build a whole different bond with the players,” Alvord says.

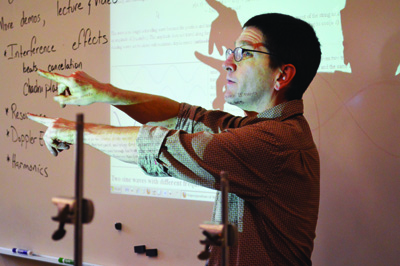

Kelly says there are other ways schools can help students get to know the coaches and their teams. This is something he has looked forward to and is disappointed not see happening. He remembers assemblies where the band was playing, there were activities and the coach would come out and talk to the students about his team.

“I really don’t feel like the school knows who I am at this point,” Kelly says. “The school just needs to show the students what’s going on.”

Dylan Wright, a junior soccer player, worked hard to gather his friends and classmates for soccer games last fall, making flyers for the hallways and Facebook events for every game. He believes it should come from one place. “The kids need to take it on,” Wright says.