It’s 3 a.m. on a Saturday morning. While most of his peers are sound asleep, Grant High School senior William Haley packs up his water bottle and rain gear and heads out to the 142nd Fighter Wing Oregon Air National Guard Base for his first day of Civil Air Patrol, a youth training program for future Air Force leaders.

As Haley enters his assigned area in medical prep, he hears the alarms blare.

He rushes over to the designated meeting spot as the sound of gunshots and mortars follow closely behind him.

Turning a corner, an explosion rings in his ears and he drops to the pavement as quickly as he can. Looking up from the ground, he sees that the sirens have stopped. Haley’s made it through his first simulation with only a few scrapes.

Haley, who has Asperger Syndrome, grew up facing intense bullying. But that all changed his sophomore year, when he joined the Grant yearbook and found a place in the CAP community. He felt a sense of dignity as the fourth generation in his family to pursue a life in the military.

Now, as his final year comes to end, Haley is preparing himself for Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps at Portland State University. After a stint in the Air Force, he hopes to someday return as a teacher to Grant, where he developed his self-pride.

Haley was born in Portland the day after Christmas in 1997. As a child, he remembers being captivated by his grandfather’s war stories: mistaking anacondas for logs in Vietnam, being taught how to survive nuclear attacks. “His stories really stuck out to me,” Haley recalls. “My grandfather is like a father. It was a huge influence having two fathers in my life.”

When Haley started attending a small, private Catholic school in first grade, “the bullying started pretty much immediately,” says his mother, Tiffany Haley. “Since Will (has) Asperger’s, he had a harder time fitting in with such a small class. Some kids were quick to pick up on that.”

Haley says it was tough not knowing anyone when he started school. “I remember being locked in the bathrooms at lunch,” he says. “The kids would put a door stop under the door and I was a pretty small kid back then, so I couldn’t get myself out.”

By the end of sixth grade, Haley’s parents decided to transfer him to Laurelhurst School, where he spent the remainder of his middle school education.

When Haley came to Grant in 2011, he slowly began to come out of his shell by the beginning of sophomore year. He became “the mascot of yearbook,” says English teacher Dylan Leeman, the yearbook advisor at the time.

That year, Haley joined the Civil Air Patrol. “I always wanted to be in the military,” he says. “Since I was a little kid, it’s kind of just been engrained in me.”

Haley began training every Monday and two weekends a month, learning aeronautic science and computer programming as well as basic survival skills.

On the roughest days, Haley was at the mercy of random attack simulations and harsh drills. “We weren’t allowed a watch and we trained surrounded by white walls,” he recalls. “We never had any idea what was going on.”

As Haley progressed in the program, he rose to be the sergeant leader of an element, commanding eight younger students in their basic drills and training. He stepped down after two years to focus on finishing his last year strong with yearbook.

Haley served as managing editor and ran most of the organizational aspects of the production. “A lot of people don’t see how much he is actually doing,” says Abby Diebold, the yearbook’s editor-in-chief. “Will’s the kind of person who will see what needs to be done and do it without complaining or asking for credit.”

Now, with the yearbook finished, Haley looks to his future plans in the PSU ROTC program with excitement. Despite his family’s history of serving in the military, Haley’s mother still worries about sending him off post-graduation.

“Having Asperger’s comes (with) different characteristics that aren’t always easy for people to accept,” says Tiffany Haley. Nevertheless, she recognizes that the decision ultimately lies in her son’s hands. “If you have a passion for something and you really, really know what you want to do…then maybe you can make it work,” she says. “I think he really needs to figure out William first…and figure out if the military is going to make sense.”

Haley’s father, who served during the Gulf War, has full faith that his son will benefit from his time in the military. “Will has a relatively easy time being part of an organization,” he says. “He comes from a family where a majority of the people served in the military. It’s familiar to him.”

With four years ahead at PSU and a hopeful two tours in the Air Force, Haley plans on returning to Grant as a history teacher after he’s finished his role in the military.

“If there’s anything I’ve learned from being in a military family more than the job…it’s doing it for the guy next to you,” he says. “I try to get that across to younger students, that you don’t have to be the best. You just have to be the best to each other.”◊

“I like that dependence, that camaraderie, because I haven’t gotten it anywhere else.” – Zoe Boyd

Grant senior Zoe Boyd sits in her room as her family members tell stories of her childhood. Her mother, Emily Boyd, suddenly pauses mid-story, letting the weight of the scene hit her. A lot has changed in her daughter.

Boyd reflects on her future plans and the room is still only for a second before her family chimes in again. She lets them speak, knowing that moments like this are soon to be limited.

Living in a constant state of relocation, Zoe Boyd always struggled to find her roots as a child. With her father absent and as the daughter of a Latina teen mom, Boyd faced racism. By age 10, Boyd had lived in four different cities as she and her mother moved across the Midwest in search of the next cheap apartment.

Now, as she finishes high school, Boyd plans to pursue an alternative route to college. In July, she will begin training to become a cryptologic linguist – a field that she hopes will finally give her the sense of community she has been searching for her whole life.

Growing up with a single working mom, Boyd frequently bumped against the walls of poverty. “My mom did her best in those times like all parents would,” she says. “Sometimes, we would eat the same food for two weeks because we couldn’t afford anything else.”

As a young family of two, Boyd remembers getting dirty looks almost every time they went out in public. “I didn’t get it – why people judged us,” says Boyd. “I think it was a combination of my mom’s dark skin and the fact that she was a teen mom.”

Emily Boyd remembers this well. “People weren’t very nice to people who looked like me and had a tiny baby,” she says. “But I was used to the comments by then…By the time she was born, I didn’t care what people said.”

When Zoe Boyd was 9, they left the Midwest so her mom could pursue a graduate program.

While finishing her education in Rhode Island, Emily Boyd’s busy schedule was tough on her daughter. “I loved my mom. She was the only thing I had in my life,” recalls Boyd. “I wasn’t very supervised…I kind of just felt lonely.”

After an offer from her parents, Emily decided to send her daughter to live with them in Missouri.

But after six months away from her daughter, Emily left graduate school in Rhode Island, and moved with Boyd to Portland.

During her first year in Portland, Boyd attended Boise-Eliot Middle School. There, she struggled with a different kind of racial issue than she was used to. “I went from being degraded for having skin too dark to being degraded for having too much white in me,” she says.

In a school with a majority of African-American students, Boyd says she was singled out for her fair appearance, as well as her mother’s sexual orientation. “Kids were calling me gay because my mom’s gay. I just said I didn’t care because that wasn’t a bad thing,” Zoe Boyd says.

But other students didn’t let up and Boyd remembers the fights that followed. “When I stood up for my mom once, a girl pushed me and beat me up,” she remembers. “I kept yelling at her while she hit me because I was so angry.”

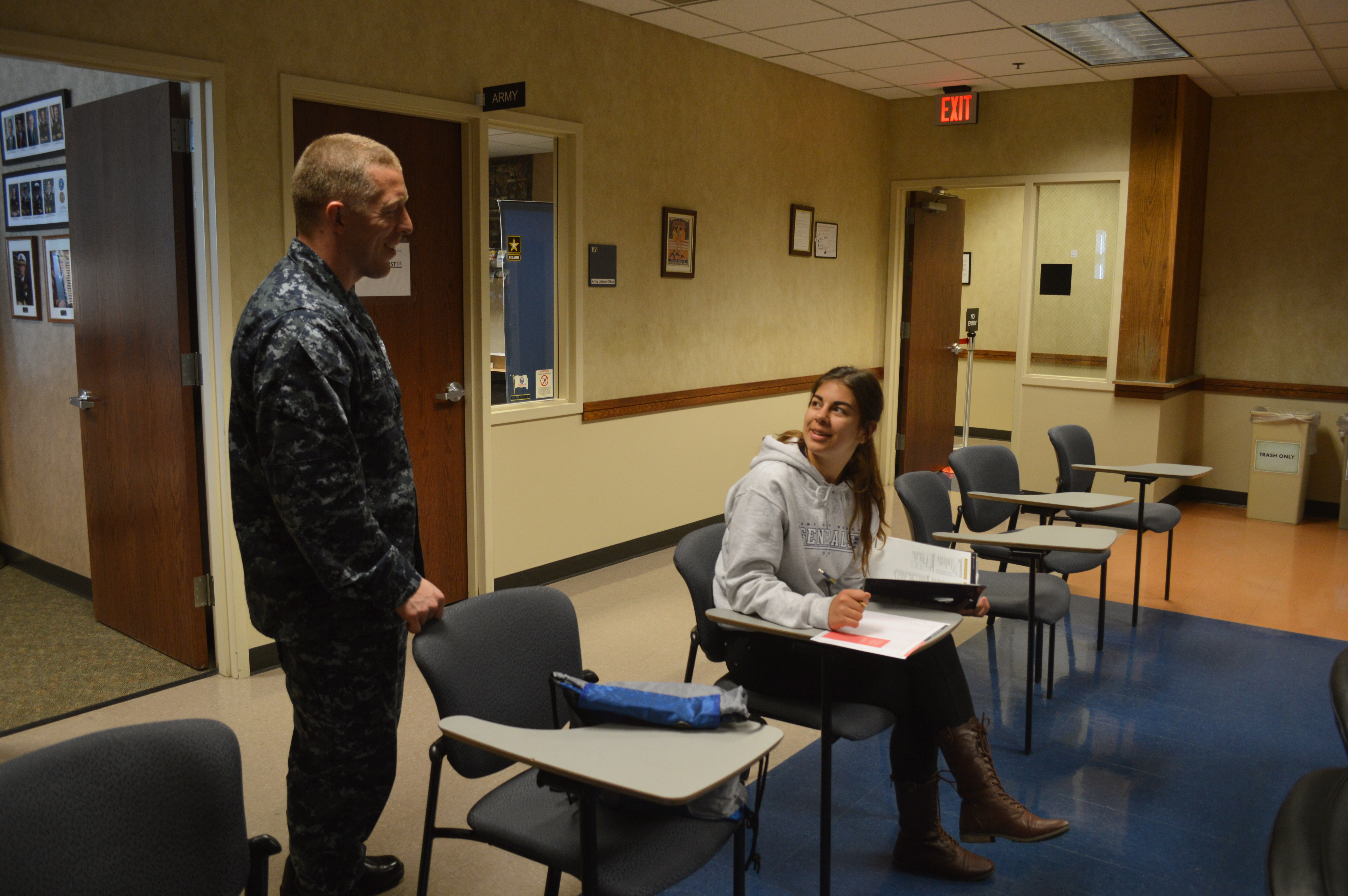

When she got to Grant in 2011, she began to search for alternatives to college. With a growing love for language, she gravitated towards a career as a cryptologic linguist for the Navy. After talking with a relative that works in the same position, she learned of the intense training it

requires, but wasn’t discouraged by the hard work.

“Zoe was raised to know that she wasn’t going to sit around the house and do nothing,” Emily Boyd says. “She was either going to work, go to school, or (do) something else productive by the time she was out of high school – or she was going to live on her own.”

Boyd was sworn in to the U.S. Navy last month and will commence training in July.

For 10 hours a day, Boyd will undertake an extremely strenuous language course. “You get two-and-a-half days off every month,” she says, “and after the first two months the teachers will stop speaking English…If you can’t keep up, you get kicked out.”

She could also be sent into military hot spots to assist with interrogations.

She fears leaving behind her family but is eager to find her path in the military.

“I lost my sense of community every time I moved, so I could never keep friends,” she says. “That’s what the military offers me: community, having comrades that you would give your life for. I like that dependence, that camaraderie, because I haven’t gotten it anywhere else.” ◊