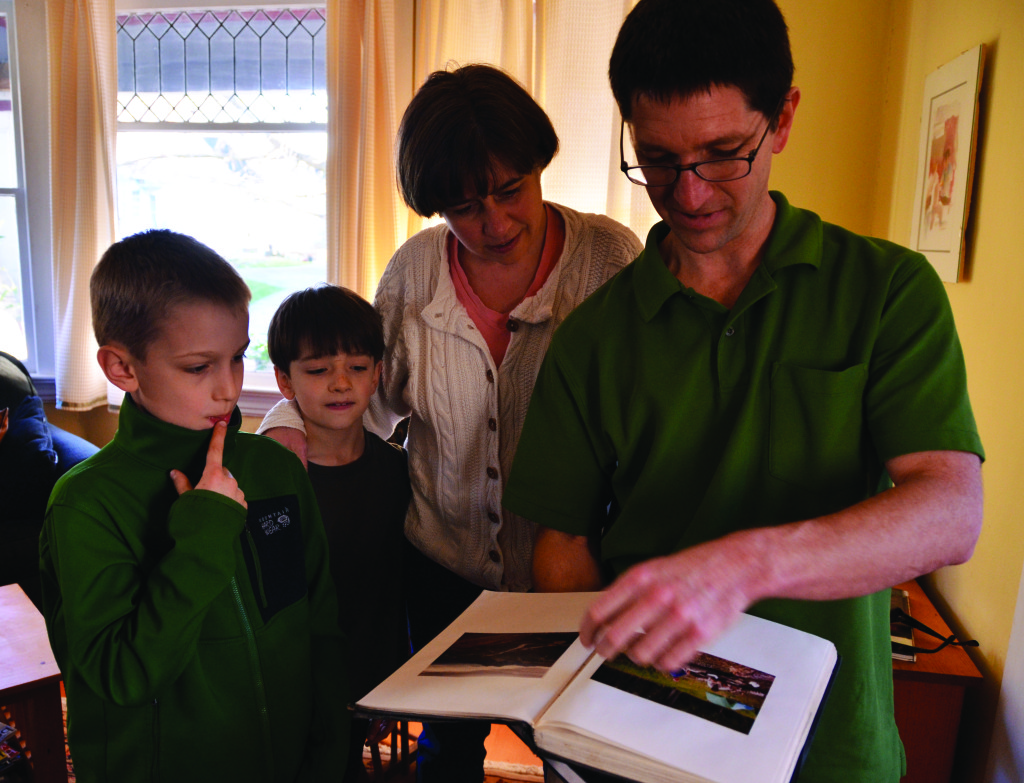

Suspended in the air, Grant High School science teacher Ethan Medley sits in a chair attached by ropes to a tree in his backyard. His two kids, Elias and Gus, watch with fascination. Medley created a pulley system to show them how a law of physics works. When he pulls on one rope, he rises higher. But in a moment of excitement, he pulls the wrong rope and crashes to the ground. He broke his collarbone, but suffered no permanent damage.

Medley isn’t afraid of an adventure. When he chained himself to a gate trying to stop logging in Oregon, he believed that was the kind of thing he wanted to do his whole life. 24 years later, Medley’s desire to make a difference hasn’t ebbed, he just focuses it on something else: teaching.

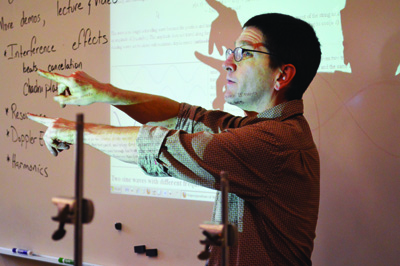

If he can teach his students to think critically for themselves and be skeptical, then that will be his contribution to the next generation, Medley says. His enthusiasm and commitment to teaching show. Students say his energy gets them excited about science. While Medley isn’t looking to embark on any big adventures any time soon, he is certainly still willing to enjoy the small ones with his family and students at Grant.

Medley grew up in Tulsa, Okla., the oldest of three siblings. Raised in the south by a religious family, his parents tried to instill in him their conservative and Christian values. His mom took him to church every Sunday and his father often talked to him about trickle down economics, a strongly conservative economic policy. “There’s elements there that I took my own spin on,” says Medley, who despite his upbringing is now non-religious and liberal.

He remembers a day when his father made him sit down and watch a Milton Friedman movie that matched his father’s views on economics. “He thought that all I had to do was understand it and then the persuasive power behind it would be all that it took,” he says. That didn’t turn out to be the case for Medley, and his dad accepts that. “He was interested in me understanding at least, if not adopting them.”

Medley says in addition to teaching him about conservative economic policies, his father encouraged him to think about things systematically and told him he could answer any question if only he thought it through thoroughly. His parents “would try to get us to think about things even if they didn’t know the answer.”

His father still sends him a copy of a conservative newspaper every week. “I might be liberal, but I’m not an uninformed liberal,” says Medley. “I appreciate hearing his view. I have a tough time seeing things in black and white because of that.”

Medley says he doesn’t know how he ended up a liberal. “Was it reading comic books and sort of internalizing this go getter stuff?” he wonders. “Was it growing up Christian? Or was it just rebelliousness and my parents were Republicans and I was going to be a liberal? I don’t know. I think my parents are curious, too.”

Maybe, he thinks, it was a combination of all three.

As a kid, Medley was normally not allowed to watch television, but his parents made an exception every Saturday night and let the kids watch Monty Python and Doctor Who, shows Medley credits for his quirky sense of humor.

In elementary and middle school, Medley says he was a typical nerd. He was the shy kid who loved to read science fiction novels, play Dungeons and Dragons with friends and walk to the comic book store during lunch.

He wasn’t interested in girls until most of his friends had started dating. Medley remembers being shocked when one day in the fifth grade his best friend got a girlfriend. “It was not on my radar at all,” he says. “I wanted to chase each other around with sticks. It was the loss of a friend.”

Medley attended Booker T. Washington High School, a school with a strong reputation and an integrated student body. His parents sent him there to surround him with other students who were academically motivated.

Medley’s high school science teacher was the first person to turn him on to physics by asking open-ended questions Medley loved to puzzle out. The teacher was a character and would often tell crazy stories about his life, claiming to be a railroad engineer and a tank driver in addition to a teacher, stories Medley says added an entertainment value to the class. “We never really knew what to do with those stories,” he says. The stories got to be so implausible that Medley started to create a mental list counting the number of lives the teacher claimed to have.

Medley attended Rice University in Houston. The school seemed like the obvious choice: “It made sense from a pragmatic view. It was cheap, strong in the areas I was interested in and it wasn’t that far away.”

Going into college he considered multiple majors, including Russian, which he had studied in high school, and physics and English. “My family wanted to make sure that I would choose a career that would get me a job. I had internalized that,” he says.

He decided to double major in physics and Russian because he knew a degree in physics would help him in the future. Houston turned out to be more conservative than Medley expected. His freshman year, he joined the Central American Interest Club to advocate for Latin American rights. Shortly after he joined, the club was attacked by other students at Rice for being “too liberal” and they tried to disband it. Medley was so put off that he lived off campus his sophomore year.

The summer between his junior and senior year, Medley decided to rebel against the broadly Republican student body by joining an environmental activist group called Earth First. He traveled to New Mexico with the group to camp in the Jemez National Forest for an annual summer training workshop for activists around the country. Medley says he was fed up with the conservative atmosphere at Rice and needed a change. “There were great people and it was stuff I was excited about,” he recalls.

The summer between his junior and senior year, Medley decided to rebel against the broadly Republican student body by joining an environmental activist group called Earth First. He traveled to New Mexico with the group to camp in the Jemez National Forest for an annual summer training workshop for activists around the country. Medley says he was fed up with the conservative atmosphere at Rice and needed a change. “There were great people and it was stuff I was excited about,” he recalls.

When the group traveled to Oregon to try to stop commercial logging, Medley says he didn’t know how much he would participate in their protests. But when the time came, he wanted to contribute. He chained himself to a gate by locking a bicycle U-lock around his neck in protest of the logging. He was arrested.

The campaign was “sort of a blunder that wasn’t particularly well organized,” remembers Medley. The point was not simply to stop logging for a day, but to raise awareness about an important issue. He says in theory their actions could have done so, “but the state was so polarized about logging already that there weren’t that many people that were shocked to find out people (were) willing to risk arrest for it.”

Medley says when the police arrived at the protest there was no easy way to remove the bicycle lock, so they had to take apart the entire gate to remove him. At the jail, Medley signed in as John Doe. He had planned to be arrested and had left his wallet and ID at home. He had his mug shot and fingerprints taken and was given an orange polyester suit to wear that read “jail” on the back. He was tossed into a gym the size of two basketball courts where he slept on mats used for tumbling exercises for two weeks. They received blankets and pillows at night, but Medley says it was cramped.

Eventually, he was let out while he waited for a court appearance. While waiting for his hearing, he climbed Mt. St. Helens and fell in love with the Northwest. He returned to Houston, where he completed his senior year of college, but he didn’t forget the experience. “It was an adventure,” he says. “It was a time in my life where it was really one thing after another.”

After graduating from Rice University in 1990, Medley traveled to British Columbia to work on a farm. He had read Wendell Berry’s book What Are People For?, which preaches the value of living an agrarian life. Medley says it gave him ideas he felt he needed to pursue and farming was one of them. “It was one of those books that sort of put into words what I had been thinking about and sort of connected all the dots for me,” he says. “It was enough to make me think ‘Wow, I should give that a try.’”

What was he looking for? “Direction. Purpose. Meaning,” he says. “I knew I could do more and that I hadn’t yet found what I wanted to do.”

Medley tracked down an apprenticeship opportunity on an organic farm with 12 other people. He milked cows and goats, raised sheep, grew vegetables and butchered chickens. “It ended up being this sort of hippie commune group,” he laughs. “I sort of decided there wasn’t a future there.” Medley says it was great to try it, but the economy was too “sketchy” for him.

Medley started an education training program before living on the farm, and he says it confirmed to him he wanted to become a teacher. “All along, this apprentice thing was just an itch that I had to scratch before I committed to teaching fully,” he says.

During the time he was working on the farm, Medley traveled to Portland and stayed with friends while he checked out available education programs. He liked what he found and decided to move to Portland in 1992.

Before becoming a teacher, he spent two seasons at Outdoor School as a resource instructor at Trout Creek. It was a good “warm up” for being a teacher, he says.

Medley got his master’s in education from Portland State University in 1994 and completed his student teaching at Roosevelt High School the same year. He was recruited to Jefferson in 1995 for two years and then transferred to Franklin in 1997.

Medley met his wife, Vicky Martell, in 1998 at a solstice party for Community Supported Agriculture members on Sauvie Island. The two immediately hit it off: Vicky was also interested in saving the environment and sustainable agriculture, and they both worked for Portland Public Schools.

“I remember feeling very bold at the end of the party,” says Vicky Medley. “I handed him my business card and thought, ‘he seems like a nice enough guy.’”

“I remember feeling very bold at the end of the party,” says Vicky Medley. “I handed him my business card and thought, ‘he seems like a nice enough guy.’”

On Monday, he called her and asked her out for dinner. “I remember leaving that dinner and thinking, ‘Oh my gosh, I just met my husband,’” Vicky Medley says.

The two wrote letters back and forth to be a couple. “I never believed in that story until it happened. You know, that like, ‘You know when you meet the one.’ You will.”

Medley agrees. “We knew really soon that we would get married. We were both at a point in our lives where we wanted to get married and have kids. I knew that I wanted to have a more permanent relationship. At that point, that was the biggest thing missing in my life,” he remembers. “It was a good match. We both wanted to make a difference.”

The two waited a year before getting engaged and then married the following summer of 2000. For their honeymoon, they traveled to Honduras, where they lived for a year. The trip matched their adventurous aspirations. They lived at an orphanage teaching 500 abandoned children to read and speak English.

Ethan Medley taught elementary and middle school students and Vicky Medley developed an internship program for high school students. “They loved him,” says Vicky Medley. “‘Ethan, fix my locker. Ethan, help me with my homework. Ethan, kill this cockroach.’ He was one of the few men in their daily lives. It was very sweet.”

They started a family when Elias, now 11, was born in early 2002. Gus, now nine, was born shortly after in 2003.

Ethan Medley was glad to come to Grant in 2007 because the school was in his neighborhood. Also, he didn’t want a job just to earn a living. “I had developed a sort of rebelling against my dad’s repeated emphasis on making money and having a comfortable life,” he says. “I think there’s a side of me that thinks ‘No, it’s got to be more than just that.’”

He says teaching can be more than that because he can nurture the next generation.

“I guess I’ve sort of taken on an ownership to make sure that they are careful thinkers and able to think critically. I don’t need people to think any particular way, but I need people to think well,” he explains. “I think of that as my share and ability to make a change for the future.”

Medley says he didn’t realize how much teaching would satisfy him by challenging him intellectually. As a career, he says, “I can’t be an activist, but with teaching maybe I can make a difference.”

At home, his sons are “a lot like me,” he says, with both favoring science, reading, the outdoors, magic and fantasy games. Medley’s wife is Catholic and they are raising the kids under the religion. “I’m just keeping my mouth shut,” says Medley, laughing and adding, “but not really.”

Medley believes, like his father taught him, that it’s our duty as good thinkers to be skeptics. He tries to instill in his kids his environmentalist beliefs by showing them how important the wilderness is. He frequently takes them on hikes in the Columbia River Gorge. The two children attend the Portland Village Waldorf charter school where a value is placed on the outdoors, and computers and other technology are discouraged.

In 2003, Medley was nominated for and won the competitive Oregon Presidential Award for Excellence in Science Teaching and received $10,000 and a trip to Washington, D. C. to meet the president. These days in class, he spends a lot of time making sure that science comes to life for his students. They appreciate his efforts to use examples that make science seem real and applicable to real life.

He recognizes his life has changed, but at his core he is still the same person. “I’m certainly not looking for adventure in the way I used to be, and it is partly because I am really satisfied with my life,” he says. “Those were good things to be doing at the time, I don’t regret them.”