Over the last several months, the Portland Public Schools community has been entrenched in legal wrangling, hostile public meetings and an investigation into how skyrocketing levels of lead in water pipes went unnoticed in nearly 100 schools across the city.

School district officials recently released the water quality results from each building, including Grant.

The findings for the Northeast Portland school are laid out in a 14-page document that show levels of lead and copper in samples taken from every faucet, shower head, spigot and drinking fountain in and around Grant. Nearly every page is marked with yellow highlighter indicating samples containing lead levels that exceed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s action level of 15 parts per billion.

In all, 105 of Grant’s water fixtures produced samples with elevated lead levels, including multiple drinking fountains and kitchen sinks. Among the affected fixtures, one result stood out in particular: a sample taken from a sink faucet in a second-floor classroom tested at 57,600 ppb, the highest level of lead measured in any water fixture across PPS.

That’s nearly 4,000 times the EPA action level.

Grant is one of 97 buildings that PPS administrators have published water quality results for this summer, 96 of which had at least one location with elevated lead levels.

Lead, a toxic metal, often seeps into drinking water from older plumbing. In many cases, high lead levels are caused by solder that joins pipes or from older brass fixtures that contain lead. Even lead contamination in drinking water below the EPA’s action can cause damage to the health of those exposed.

Although the results sound extreme, when compared to other PPS high schools, it’s clear the scale of Grant’s lead issues isn’t an outlier.

Cleveland, Jefferson and Alliance High School at Meek all have a larger number of affected fixtures. Marshall, the school Grant students will occupy beginning next school year for two years during the upcoming remodel, contains more elevated lead levels than any other building in the district with 255 locations surpassing 15 ppb.

“I can’t say that I’m extremely surprised because the building is old,” says Principal Carol Campbell. “My biggest concern is places where people would be drinking the water.”

More worrisome than results from the high schools is the large number of elementary schools on the list. Elementary-age children are especially vulnerable to lead’s toxic and long-term health effects. One potential medical issue that can arise is damage to the nervous system that causes developmental delays and learning difficulties.

The plan for district-wide testing was announced last June after a release of documents showed high levels of lead were found at 47 PPS buildings, including Grant, between 2010 and 2012.

The latest tests, performed by TRC Solutions, reveal an urgent and systematic lead issue throughout the district. The results have left students, teachers and parents worried. Many are criticizing the district for a lapse in communication and a poor response around handling the 2010-2012 lead test results.

“It seems like there was just a lack of transparency in what was going on…Obviously things weren’t handled quite right,” says Jolene McGee, the mother of a Grant freshman.

Under high levels of scrutiny, numerous PPS employees lost their jobs, and superintendent Carole Smith was forced to step down in disgrace. With district leadership in transition and a lead problem growing in severity, PPS is heading into the 2016-2017 school year on shaky footing.

No one has been chosen to permanently replace Smith and the district’s school board is trying to stabilize leadership at Oregon’s largest school district.

“I think it’s kind of the district’s fault,” says Leo Oudomphong, a Grant sophomore. “They really need to take action.”

To many, the district-wide issue is reminiscent of the ongoing water crisis in Flint, Mich., which poses a serious public health danger to thousands of children.

But large-scale water contaminations only account for a small portion of an estimated 500,000 U.S. lead poisoning cases annually. Most often, the source of exposure lies in lead paint of individual homes.

“Somewhere around half a million kids are still getting elevated blood lead levels above the public health action level…in this country annually,” says Perry Cabot, a senior program specialist with Multnomah County’s Healthy Homes and Communities Program. “Most of these exposures are related to paint.”

Lead poisoning, Cabot says, is “the number one environmental health hazard” for children in the U.S.

Exposure to lead is often concentrated in areas where low-income or people of color are concentrated. Most susceptible are residents living in public housing with old, crumbling infrastructure. This causes a racial and socioeconomic disparity for those who face the disastrous consequences of continuous lead exposure.

“There is definitely a disproportionate impact on certain racial and ethnic groups,” says Cabot, who cites that African-American children are three times more likely to have elevated levels of lead in their blood than white children.

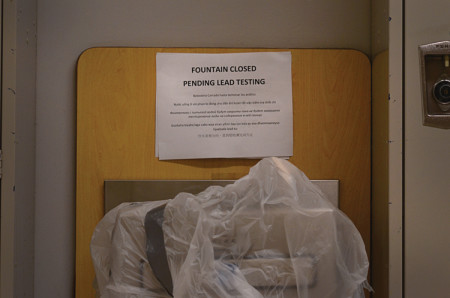

For PPS, issues surrounding water quality first came to light last May when district parents were informed of elevated lead levels found at Rose City Park and Creston elementary schools, nearly a month after the initial testing. The district apologized for not following federal rules when testing occurs and announced they would shut off all drinking fountains for the remainder of the school year and provide bottled water for drinking and food preparation.

On May 31, the same day bottled water became available to schools, the Willamette Week newspaper published a story based on documents obtained through a public records request. The story revealed that between 2010 and 2012, 47 schools were discovered to have elevated levels of lead.

Previously, PPS officials had said there hadn’t been testing since 2001. Although emails showed district employees discussing putting labels on affected fixtures in 2012, no action was taken. Carole Smith and other high-ranking district officials denied any knowledge of the tests, and calls for her ouster increased.

The release of other internal communications shows PPS had multiple mishaps with filter installation and maintenance on water fountains. Another email conversation among district officials shows a decision was made against labeling lead-contaminated water fountains in order to prevent public panic.

Cabot says responses like these don’t match federal protocols for handling such situations. “It’s not in good alignment with what the EPA would expect or wish for in this case,” he says.

In early June, PPS announced it would perform comprehensive lead testing at all buildings during the summer. Many Grant students and staff believed this was a precautionary measure that would only reveal a small-scale contamination within the water system.

“I thought it would be solved in a week, like one of the minor problems that always happens at Grant,” says junior Marcel Bull.

That perception disappeared when Grant’s results were published. The 57,600 ppb reading is even more than the highest level measured in Flint.

“I thought it was a typo,” McGee says of the result. “That’s ridiculous … if anyone drank out of that, it’s certainly a huge concern.”

Cabot says it’s possible the reading is a fluke, suggesting a small piece of lead solder could have contaminated the sample and drastically increased the result. PPS officials say they will retest fixtures with extremely high levels in the near future.

Overall, the test results may not paint an accurate picture of the water that was consumed on a day-to-day basis. The tests used samples taken immediately after turning faucets on after being unused for an extended period. Running the faucet for only a short time can dramatically decrease lead levels.

Out of 628 people screened, five students and two employees have tested positive for elevated levels of lead in their blood. It’s unclear if any of these people work or go to school at Grant. Medical information on individuals is private.

These cases aren’t confirmed, and there’s no clear link between PPS water and lead poisoning, officials say.

“I suspect … that the odds are that the home is the most likely contributing factor,” says Cabot, but adds: “We will not rule out any location as a contributing factor until we’ve completed our investigation.”

Still, the possibility of negative health effects conjures up fear among Grant students and staff.

“It’s terrifying,” says Bull, who admits to drinking water from Grant taps on a regular basis. “It makes me really question my health. I think I’m OK, but at the same time, I don’t know.”

PPS has pledged to provide drinking water until it can be ensured that fixtures have levels of lead below the EPA threshold. At Grant, it doesn’t seem probable that solutions will come in the near future.

“I think we’ll have bottled water all year,” says Campbell. “I don’t think they’ll do anything major construction- wise or replacing plumbing because we’re going to be remodeled.”

The district will implement water dispensers to reduce waste, she says. Whatever happens, it’s clear the district has a long way to go before any level of trust comes back. “I definitely feel way more distrust,” says Bull. “PPS as a whole hasn’t lived up to my expectations. We’re ingesting this stuff, and it’s somebody’s fault.” ◊

Visual Representation of the Water Fixtures with Unsafe Lead Levels

The larger circles show water fixtures with higher lead levels and the color scheme helps identify what type of water fixture was contaminated.