Grant senior Ruben Estrada was in the middle of studying at Portland State University when he found out the news. His day had started out normal, but within moments it would be transformed into one of particular significance. All his hard work during high school was about to pay off.

Adam Ristick, the Portland director of the Act Six scholarship program, was on the phone. Estrada had especially impressed him in a recent interview, Ristick told him.

His most impressive feature, Ristick said, was his perseverance. As a result, Estrada was awarded an Act Six scholarship – a full ride to Warner Pacific College.

Estrada was born in Santiago de Cuba, the second largest city in Cuba. He moved to the United States when he was 15. His parents, José Luis and Yamelis Herrera, relocated the family because they wanted easier access to new opportunities. But upon arrival, the dreams weren’t easily obtained.

Coming in with little knowledge of the English language, Estrada’s family met the consequences of a language barrier in America right away. Estrada refused to let that hinder his goals from the start.

“I couldn’t talk to my classmates. I felt isolated, like I couldn’t do anything.” – Ruben Estrada

Growing up, Estrada loved Cuba and today he still wears a necklace with the Cuban flag around his neck. But his parents had higher aspirations than the education system the country offered. They believed that America would allow their children to choose their own career path and be recognized for their hard work.

“I came into this country because I wanted better opportunities for Ruben and his sister,” says Luis. “I left behind everything I had – friends and work – because I wanted them to go to college here in U.S. and get a higher level of education.”

Estrada’s parents broke the news about their decision to move in 2009, and by 2011 the family had arrived in Portland. They later attained Green Cards to stay. Upon arrival, it was summertime, which Estrada says made the transition a little smoother.

“When I came here, everything was like Cuba – you go out, you play soccer, you play basketball, you go to the pool, you have fun,” he recalls.

But once fall came and school started, reality set in. At Grant, Estrada tried his hardest not to stick out. He kept to the school walls and rarely asked questions in class. He also enrolled a year behind, which meant that he joined Grant as a freshman when he should’ve been in 10th grade.

But this turned out well for Estrada, who had to adjust to a new teaching style, culture and language all at once.

“I couldn’t actually communicate with anybody when I came here,” Estrada says. “I couldn’t do whatever I want. I couldn’t do well in classes. I couldn’t go out with friends. I couldn’t get good grades.”

Academic pressures alone weren’t new to Estrada, though. In Cuba, Estrada says the grades are all based on the conclusions, not the thought processes. He remembers thinking the standards were extremely high.

At Grant, it was mostly the language barrier that gave him trouble. “I couldn’t find any ways to be successful in my classes because I couldn’t talk to my teacher,” he remembers. “I couldn’t talk to my classmates. I felt isolated, like I couldn’t do anything.”

Estrada was unable to participate in class as much as his peers, so his grades suffered. Herrera remembers parent-teacher conferences with her son’s teachers being particularly rough. Most of the time, the conversations ended with her in tears.

“But I knew he was smart,” she says in her native Spanish. “So I just cried and cried.”

Some experts estimate that more than half of the immigrant population in the U.S. can’t speak English at a level considered to be proficient.

Dr. Óscar Fernández, an assistant professor of Spanish at Portland State University, says that’s partly due to it being difficult for adults to learn a new language as they age. And if those adults work in immigrant communities that speak their native languages, such as Estrada’s parents, English is even less of a necessity.

But this situation can adversely affect the children.

“If our parents don’t speak English, they can’t be very helpful with our homework assignments,” says Fernández, who immigrated from Costa Rica. “They can’t be very helpful with filling out applications, and that also impacts how successful the student might be because the bilingual student will have to do pretty much all the legwork; whereas in other families where English is the first language the parent can help a little bit.”

Estrada says his Grant English as a Second Language teacher Marta Repollet helped fill this gap. “She’s kind of like my mom at the school,” he says with a laugh.

“Ruben has worked harder than any student I remember in recent history to overcome the language barriers standing between him and his educational and career goals,” says Repollet. “He possesses leadership skills, commitment and passion to support other English language learners like himself.”

By his junior year, Estrada was comfortable enough to involve himself with education in more ways. He joined Upward Bound, a program run through PSU that’s designed to help disadvantaged students through high school and prepare them for college.

“He always makes himself available to other students,” says Upward Bound advisor Darryl Kelley. “If they get an assignment, they can come in and he’ll explain and help them get caught up…He’s super helpful, just a great community mentor.”

Estrada also joined the International Youth Leadership Conference High School Leadership Council, an organization run through Portland Public Schools. The group focuses on improving school life for ESL students. Estrada took this opportunity to reach out to others in the high school immigrant community as well.

“He actually introduced me to this country,” says Saimon Asghedom, who is also a senior at Grant and a member of the council. “He was the first friend I made. We were in an ESL class…and he just talked to me and stuff and it just kinda went from there.”

“It can be hard to learn the language, but if you really have a purpose in your life, you can do it. Nobody can stop you.” – Ruben Estrada

Asghedom immigrated to Portland from Eritrea two-and-a-half years ago and has stuck with Estrada the whole time.

In 2014, Estrada and the leadership council brought an issue before PPS Superintendent Carole Smith. Their presentation focused on the experience of non-English speakers in PPS and how it can be improved. “ESL students don’t have the opportunity to say what they feel or how they want to do it so that is my goal,” he says. “I feel like I should do something about it. So that’s what I’m doing.”

Last school year, Career Coordinator Madeline Kokes, as well as other mentors in his life, informed Estrada of various college scholarships that they thought he should apply for. Act Six was one of them.

The Act Six program aims to “develop young, diverse leaders from diverse backgrounds,” says Ristick. “They all show leadership traits differently. Academically, at home, serving the community.”

It also gives students in Oregon and Washington a full ride to select colleges like Warner Pacific, as well as access to supplementary life skills workshops.

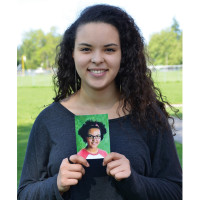

When Ristick called Estrada that day in the PSU classroom, Estrada was hard at work preparing for college with Upward Bound. After he found out he had been accepted to the Act Six program, he was ecstatic and quickly shared the information with his friends and family.

“It’s the chance of a lifetime and it’s gonna change his life and set him on his path,” says Kokes.

Estrada is eager to show what he can do. “I feel proud because I’m gonna help my family and I’m gonna improve my community,” he says. “I love to deal with people and help them to have a better life. And that’s what I’m gonna do with the scholarship.”

He’s managed to keep himself constantly busy. Typically, Estrada leaves Grant around 4 p.m. after asking his teachers questions or talking with friends and heads to Upward Bound activities. On Mondays, he also attends scholarship workshops in the evenings.

On most nights, Estrada tries to have his homework done before he hangs out with friends. And on Fridays and Saturdays, he can be found working late nights as a guest service attendant for the Nines Hotel in downtown Portland. He tries to clear Sundays as a day to relax.

Starting this fall, Estrada will be studying biomedical engineering at Warner Pacific. He will be the first member of his family to go to college. “I want my sister to have a role model to go to college and to do whatever she wants and achieve her dreams,”

he says.

But he also feels like he has a responsibility to the immigrant community as a whole. “They can go to college and study whatever they want,” he says. “They feel intimidated because they don’t know the language. But if they want to be a doctor, they can be a doctor. If they want to be an engineer, they can be an engineer.

“It can be hard to learn the language, but if you really have a purpose in your life, you can do it. Nobody can stop you.” ◊