It was around mid-March when Grant High School administrators discovered that a ring of more than half a dozen freshman boys posted racist, misogynistic, homophobic and other offensive content on social media.

The boys’ action – which authorities believe started as early as last September – painted an ugly picture: a photo of a black Grant student with racist descriptions attached; texts back and forth spewing anti-gay sentiments; and pictures of battered women with captions encouraging men to do more damage.

A student complained and an administration-led investigation ensued. The boys – all white – faced discipline ranging from suspension to expulsion. But less than a week after spring break, all except one of the boys were back at Grant.

It wasn’t until Grant Magazine broke the story on its website the day after the boys returned to school that most people in the community knew anything had transpired.

Grant’s administration braced for the worst as local news media chased the story, bringing headlines and satellite trucks to the campus. The frenzy lasted a few days and district officials remained silent, citing student privacy rules.

Inside the school, curiosity over what happened grew. Students talked openly about the boys, speculated on what their motives were and reeled at the disparaging messages they sent. Some were appalled by the posts. Others felt like the boys had a right to exercise their free speech.

But in classrooms at Grant, the issue was barely discussed until after the investigation had closed. Initially, teachers were specifically instructed not to bring up issues of racism, homophobia and other topics tangentially connected to the investigation. The reason, administrators say, was because officials wanted to make sure the accused and any victims weren’t harmed by people talking about them or knowing how they were involved.

However, a number of people in the Grant community say it was a missed opportunity to tackle some tough subjects. The administration’s handling of the recent events raises questions about how issues around race, gender and sexuality are addressed within the Grant community. Many feel that a lack of productive conversation inside the school doesn’t foster the kind of understanding necessary for students and authority figures to adequately talk about sensitive topics in a school setting.

“There are teachable moments every day in the hallway,” says Maria Scanelli, the Restorative Justice Coordinator for Resolutions Northwest, a non-profit organization that partners with Grant’s Restorative Justice team. “There are teachable moments every day in the classroom that are not being taken advantage of. And to me, that’s even more indicative of how we’re failing each other as people – both as adults to youth and as a community in general.”

Three years ago, Grant made headlines for a hazing incident in the athletic department. Midway through the basketball season, reports surfaced of apparent sexual assaults that may have happened among boys junior varsity players in the locker rooms.

No one was charged with a crime in the case but school officials were concerned enough that they eventually didn’t rehire several coaches including most who were involved with the boys program. Also, questions were raised about the culture of hazing – physically humiliating someone in way of intimidation – and its place in Grant athletics.

Vivian Orlen, Grant’s principal at the time, made the decision to talk openly about the incident, saying she was not concerned about the school’s reputation. In her mind, staying silent would’ve only painted the school in worse light. She went on public radio, encouraged Grant Magazine to write about the incidents and conducted interviews with the local media.

“I think when you’re a leader of a school, you have…to be very strategic in terms of where and how you’re going to facilitate conversations with students,” Orlen says. “So they understand what was real and not real, and how to make that productive and let students process disturbing information.”

In response to the hazing incidents, immediate action was taken. Each member of Grant’s coaching staff met with the administration to address the need to revisit supervision and harassment policies. Letters from the coaches were sent out to parents and team members acknowledging the events and setting a bar for moving forward as a community.

While this fast-paced and pointed approach proved to rub some community members the wrong way, the father of one of the hazing victims – who asked to remain anonymous for fear his son might be identified – believes transparency is key in situations like these; he would’ve liked to have seen more from the 2011-12 administration following the actual events.

“I think a lot of people didn’t exactly know what was going on, and so they kind of heard generic terms like ‘hazing’ or things like that. It kind of sounded a little more innocent,” he says. “I think if they had actually listed what had happened, I think probably fewer people would go, ‘Oh, well, that wasn’t so bad.’”

Since Orlen’s departure in 2013, school officials have taken a more conservative approach to how they address serious incidents within the community.

When a handful of students had sex in and around the school last November, some of them used social media to send videos of the incidents. Officials kept details of what happened quiet, but closed several bathrooms and also made sure that no classrooms could have unaccompanied children in them.

The administration also devised a new curriculum – that’s intended to be implemented into next year’s health classes – that centers on educating youth and parents alike about the possible repercussions of unchecked social media posting.

But little discussion followed in classrooms.

In the most recent social media investigation in March, few official discussions were facilitated by staff members. Instead, the administration – in a move to protect the accused and those who were victims of the social media blasts – made the decision not to address the issue with the whole school.

“We wanted to focus the resources that we have on the people most impacted,” says Vice Principal Kristyn Westphal. “The harm that was done happened within the freshman community. And so that’s the most direct place to address it and that’s also the segment of the Grant student body that has the most knowledge of what happened.”

The freshman community teachers were later asked to methodically approach things in their classes – first with writing prompts assigned with an outside Restorative Justice contractor and then with small discussions.

For Principal Carol Campbell, those directly involved in the incident are a top priority, not speaking with the school at large especially after such a controversy. She hopes that discussion within the upper grades will begin to manifest as the teachers see fit.

“We shared what we were able to share with teachers,” she says. “Keeping some of the information confidential…We don’t talk about some of the specifics because it could be something we don’t want everyone to know about because it’s private and it could hurt the students further if it gets out.

“So we give them information, enough information to know we had an issue and go from there.”

Yet, some feel such little information was given that educational discussions couldn’t take place.

“I, for one, don’t feel as though I could open up a discussion safely if I don’t know anything…it’s hard to have a real conversation without knowing what’s going on,” says Grant English teacher Kate Brandy. “We weren’t given any guidance. I would want to. I would absolutely want to, but I don’t feel like I could because what would happen in that case because I don’t have any information? Kids would bring information, and I wouldn’t have any way of guiding or allowing room for truth.”

Scanelli recognizes this as part of the root of Grant’s disconnect when it comes to facilitating difficult discussions. It’s the same for just about any school.

“We’re looking at generations of adults who haven’t been having these conversations in schools,” she says. “They’ve never had these conversations in the classroom…And then we’re asking them to lead them, with youth. It’s a little dangerous…So just stepping out of that paradigm is different for a lot of people…That pattern needs to be undone.”

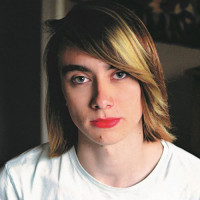

A few select Grant teachers attempted to initiate discussions with their students. Freshman English teacher Dylan Leeman, who regularly tackles controversial topics, feels the recent incident changed the climate of his classroom.

“I push my students to share their truth with the class and make it a safe space,” he says. “And then something like this comes along and just really fundamentally violates that trust in the whole class.”

Portland Public Schools Chief Equity and Diversity Officer Lolenzo Poe says he was not surprised to hear that the Grant community was shying away from immediate conversation following the social media incident. It’s a trend that he recognizes in school systems all over the country.

When an incident concerning race or gender is presented within a school setting, Poe says the community starts to question and “challenge ourselves about where we truly stand on any number of issues. So it is very uncomfortable. And it’s much easier to move to something else as opposed to really having the conversation and really looking at it and doing the self-reflection it takes to really address those kinds of issues.”

C.J. Pascoe, an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Oregon, says the discussion also stems, in part, from the history of issues deeply rooted in society.

“As a country, we have an especially hard time talking about race – in large part due to the horrific legacy of slavery,” she says. “But it’s also in part because we now operate in a post-feminist and color blind era. That is, we tend to think of problems like racism and sexism as ones that have been solved…We haven’t developed a language to talk about institutional racism or institutional sexism – that is racism and sexism that are reproduced through social structures that are larger than any one individual.”

And yet, these trends can be identified between Grant’s past three major incidents. In terms of disciplinary action following each discovery, some choose to recognize the role that race played. In the instances of the hazing incident, rumors flew that the attacks came from black players specifically against their white teammates. In the sex scandal, the boys involved were black; the girls were white.

The latest events involved students who were all white. One student was expelled, but most returned from suspensions within a week. Some teachers and students wonder aloud how the racial makeup of the students involved influences discipline.

“My hope is that white students would be punished as severely as anyone,” says Brandy. “That all students be punished the same. And I worry, in general – I don’t know about our administration – but I worry, in general, that people with advocates who are louder or stronger, who have more time, and sometimes more money, more social privilege, get listened to.”

Poe recognizes that setbacks may occur and progress may seem stagnant. But he says that’s to be expected. “The issue of race, gender and sexism has been around a lot longer, so if anyone believes you’re about to eradicate it now… I’m sorry, I just don’t see it happening,” he says.

Poe says that continual, honest discussion is only more of a necessity. “Everyone in the district should be working on their own racial consciousness and moving forward because this is not one of those things where you can go in for two trainings and three follow ups and you have it done. It doesn’t work that way,” he says.

But, the key to the disconnect is that despite once-a-month equity meetings that staff members participate in every Wednesday there’s a late start, the knowledge doesn’t always trickle down to the students.

So, even though some students are torn about where they stand – some adamant in excusing the posted comments as jokes, and others that arguing moral standards – most say that any sort of facilitated discussion would help hash out

uncomfortable thoughts, because some discussion is better than none at all.

“We don’t have conversations like (that), ever,” says freshman Deausha Spencer, who is black. “I feel like (the administration and teachers) should do that more…just 20 minutes or something; have everyone talk and ask questions and they can give us actual answers instead of hiding stuff.”

All of this comes after a near decade of Courageous Conversations – a district-wide equity training required for staff – and several meetings with Resolutions Northwest about equity in schools.

Officials acknowledge that there’s a disconnect sometimes. But it’s not for a lack of trying, they say.

“This Courageous Conversations work is just as much about yourself and your own growth and racial consciousness,” says Karl Logan, a senior director for Portland Public Schools who oversees the Grant and Jefferson school clusters. “If you’re not conscious, if you’re not aware of your own bias, that is going to affect how you interact with your own students. You’re going to teach who you are.”

Not long after Grant Magazine broke the story on the social media investigation, a substitute teacher dedicated an entire block period to discussing the specific topic with a freshman Modern World History class. For the students, the act of debating amongst themselves helped reach a level where they could then draft solutions and preventive strategies for the future.

“You could hear and feel students relax and come back to issues and change their minds when given the opportunity to discuss it slowly,” says the substitute teacher Michael Sweeney.

Sweeney allowed students to take the reins and opinions were all across the board. Some were adamant in not wanting to report or “snitch” on those close to them. Others felt that there are certain boundaries that can’t be crossed – race and gender being two of them.

For Tomas Beckett, a white freshman in the class, the conversation was purely constructive. “I think, definitely, that class is more open with each other now,” he says. “I think that because of the discussion, people are more willing to talk about stuff like that.”

Scanelli says if the school wants to make more progress breaking down the disconnect within Grant’s community around race and gender, continual conversations for both youth and adults are key.

“You’re being failed as a youth by not having those consistent conversations on a daily basis or having adults around you that interrupt you when things like this happen,” she says. “To me, that’s the bigger thing to get angry about, and that’s the bigger failure. To what point do we rally together and take responsibility for each of our roles in creating those opportunities for youth and for adults? We’re in this together.” ◊